UK is seeing the worst economic shocks, currently going through a labour shortage which is stifling its post-COVID recovery. Its trade with EU has taken a hit as costs have shot up. This is showing in UKs dwindling apparel exports to Europe, while non-EU partners have not yet provided a stable support. An analysis.

UK’s economy faced a double whammy--one of the harshest impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic along with dealing with the dramatic consequences of moving out of the European Union. Being an economy that was dependent on migrant labour from EU as well as outside EU, the gaping hole left from the massive ousting of EU workers has left a large unmet demand for labour in the most crucial sectors of the economy right now. The conflation of pent-up demand post-Covid and supply as well as labour shortages has become a perfect setting for fueling inflation and rising living costs in UK, while keeping growth muted. Estimates from the Oxford Migration Observatory and other sources put the migration of EU nationals out of UK between 42,000 and 300,000 as plausible numbers. Job losses during the pandemic led many to shift back to their native countries, and it is possible that many would not come back even when things go back to normal.

Worker shortages and economic impact

Workers from EU were mostly employed in elementary occupations (like warehouse operators, kitchen assistants and waiters), as process, plant, and machine operatives and in other low paying jobs (more than 50 per cent of the EU workers) as estimated by a UK government report in 2017. Even a starker contribution in the lower paying jobs came from EU countries except EU141 , countries which became EU members in and after 2004, which are also the less rich economies amongst EU27. Almost half of the EU82 and EU23 workers were working as process, plant, or machine operatives and in elementary occupations as opposed to only 13 per cent of EU14 nationals. Overall EU nationals were less likely than UK nationals to work in senior management levels, professional occupations, technical occupations or administerial or secretarial jobs.

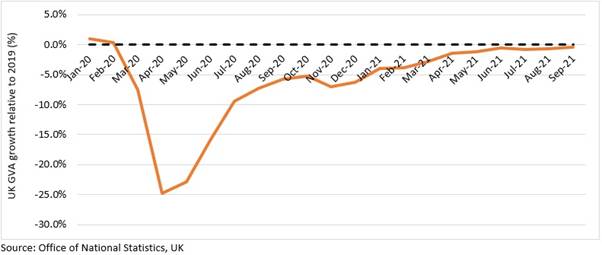

Resultantly, what you see today in the UK is a situation where workers for hospitality, social work, transport & storage, and many low skilled sectors are hard to find, and consumer prices are rising due to global supply chain issues. This keeps UK’s prospects of a quick recovery here on very slim. Economic recovery in the UK has already been slower than its G7 peers and even after three quarters of 2021, its gross value added (GVA) remains lower than levels in 2019. Figure 1 compares monthly GVA index of 2020 and 2021 to corresponding months of 2019. GVA for Sep-21 was estimated to be lower by 0.4 per cent relative to Sep-19.

Figure 1: UK GVA growth relative to 2019 (%)

On the other hand, vacancies in UK have boomed as businesses opened up due to relaxed restrictions and in the hope of a better demand this festive season. Official figures suggest vacancies have reached a multi-decade high of 1.2 million while jobs filled every month has remained flat in recent months. The gap between vacancies and jobs filled every month has therefore widened tremendously as a result (Figure 2).

Figure 2: New payroll employees and overall vacancies in UK

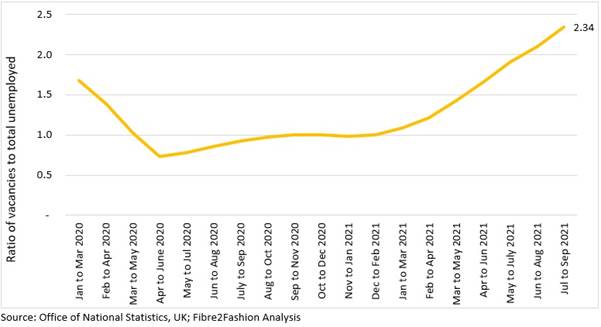

Another way to look at this, is the ratio of vacancies to unemployed people (Figure 3). This metric theoretically implies if the vacancies are more or less than the total pool of available workers for these jobs. This ratio has also moved up tremendously over the last five quarters on a rolling basis. Not surprisingly most of these vacancies are in sectors such as health & social work, accommodation & food services, retail trade, manufacturing, and transportation & storage. As we have seen these segments were dependent heavily on workers from EU, the pressures are only going to mount further.

Figure 3: Ratio of vacancies to total unemployed in UK

Transport and storage sector has become a key cog in the logistics machinery and is seeing one of the worst pressures amongst all. UKs trucking industry is probably the worst hit, as both COVID and Brexit related impact came at the same time. Road Haulage Association in the UK estimated in a survey in July-21 that overall shortage for truck drivers could be as high as 100,000 back then. The main reason cited by the respondents was, in fact, Brexit, followed by retiring drivers and drivers leaving for another country. While the government has responded to this shortage by opening temporary work visas for HGV drivers (among several others), the response to this scheme has only been limited.

This has led to supply chain impact in the form of almost ubiquitous shortage of supplies in several parts of the country. Rise in wages has also been dramatic for many industries but typically where labour shortages are high. Wages have broadly been raised to incentivise truck drivers, workers in supermarkets and construction workers to work in the UK. Higher wage inflation for lower paying jobs would likely translate into an inflationary impact on all products and prices rising consequently for everyone in the economy. Consumer price inflation in UK has already reached 3.1 per cent in Sep-21 (Figure 3) and is expected to reach 4.0 per cent by end of this year.

Figure 4: CPI inflation and median wage growth in UK

Impact on UK’s apparel exports

As much as any industry is impacted from economic shocks, the textile and clothing industry also follows the cycle. UK’s textile and clothing industry was one of the worst hit during the pandemic with many major brands either forced to re-imagine their consumer strategies or filing for bankruptcy altogether. Apart from the domestic industry and its woes, global demand for UKs apparel has also provided limited support. Textile and clothing trade for UK has not performed well over the years, as its exports market continued to lose business since 2018. UK’s textile and apparel exports have dwindled in the last two years and continue to decline this year as well.

UK’s most highly exported category, apparel, has seen a decline in flows of 41.2 per cent in Jan-Sep 2021 relative to the same period in 2018. UK’s apparel exports for YTD until September have gone down from USD 7.3 billion in 2018 to USD 4.3 billion this year. This gradual decline is across many markets but most prominent and perhaps more shocking in some of the neighbouring EU countries. Even when there are no custom tariffs on importing goods from UK to EU, a VAT of the destination country will still be levied and in some cases, customers could be charged custom duties as well (charges for providing the extra documentation to prove the rules of origin and to complete the necessary bureaucratic procedures).

It is reasonable to assume that a large part of the additional impact on UK EU trade relative to UK Non-EU trade is perhaps solely because of Brexit. UK goods have become expensive for EU both because of higher costs due to added labour costs and increased border charges. The impact is clearly visible when we compare UK apparel exports to EU vis-a-vis non-EU markets. Figure 5 shows that exports to EU which were just about 3x of non-EU apparel exports have fallen to almost similar levels since the beginning of this year. This translates to a more than 40 per cent drop in apparel export revenues for UK between 2018 and 2021. We can also see from this graph that non-EU apparel exports have recovered strongly and are now performing much better compared to pre-pandemic levels. However, that has not yet become a substitute for lost EU exports. Among the non-EU markets as well, exports to US were performing well before even the pandemic and have seen tremendous growth in 2021 growing quickly past the pre-pandemic levels. The US market has provided a much-needed cushion for UK’s apparel exports.

Figure 5: UK apparel exports to EU and non-EU partners

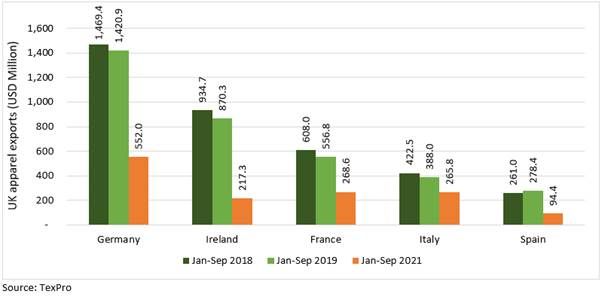

Country-wise, the largest impact in import demand has come from Germany, Ireland, France, Italy, and Spain. Germany with apparel demand of around USD 1.5 billion during Jan-Sep 2018, only bought USD 552.0 million worth of apparel from UK during Jan-Sep 2021, a massive 62.4 per cent drop. Apparel exports to Ireland also dropped by 76.8 per cent from USD 934.7 million in Jan-Sep 2018 to USD 217.3 million in Jan-Sep 2018. Exports to France, Italy and Spain saw a drop by 55.8 per cent, 37.1 per cent and 63.8 per cent respectively (Figure 6). Netherlands is perhaps the only large trading partner which saw a rise in apparel exports from UK. That is probably because Rotterdam is the biggest port in Europe and a large part (the proportion remains unknown) of apparel exports from UK were for re-exporting.

Figure 6: UK apparel exports with EU partners

Currently, there are speculations that Bank of England might raise interest rates soon due to rising inflation concerns. As much as this seems apparent from the Central Bank’s perspective, global inflation concerns are hardly a demand problem right now. With labour costs already rising for businesses across many sectors in UK, a rise in cost of capital may prove an added burden to the industry. However, a much-needed relief was recently provided by the government recently announcing a large budget support (USD 103 billion) to businesses in the form of tax discounts and providing families with income support to boost demand. That could provide the necessary push in the short-term to the limping UK economy, but the major issue remains the labour shortages. That surely has no quicker fix, and it would only be resolved when UK-EU relations see much more certainty. Clarity on labour movement, goods movement would be the surer solutions to recovery and behavioural adjustment to a sudden change in aspects of trade will likely take longer than expected to resolve themselves.

References:

1EU14: Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Republic of Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, and Sweden

2 EU8: Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Slovakia, Slovenia

3 EU2: Bulgaria, Romania

4https://www.rha.uk.net/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=ICI0CFWmVo%3D&portalid=0×tamp=1627564639720

Comments