Feb '18

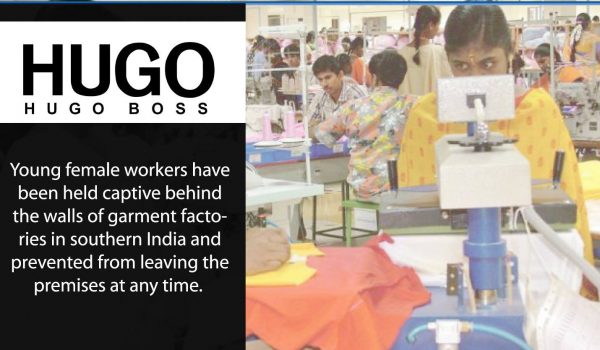

Desk Report (RMG Times) Modern slavery is still the barrier for the workers in India. Luxury fashion retailer Hugo Boss said it has found cases of forced labor, a form of modern slavery, in its supply chain. Young female workers have been held captive behind the walls of garment factories in southern India and prevented from leaving the premises at any time.

Hugo Boss, which raised concerns about the free movement of resident mill workers in its 2016 sustainability report, said it has been working to resolve the issue with local suppliers.

Following the report, a Guardian investigation into the confinement of thousands of young migrant workers on factory premises in Tamil Nadu found that Best Corporation, the company used by Hugo Boss, also supplies garments to high-street brands including Next and Mothercare.

Best Corporation is not the only company in southern India where issues relating to worker confinement exist. The policy of housing large numbers of young female migrant workers in dormitories on factory premises is widespread in the region.

Factory owners say the policy is necessary to ensure worker safety in largely rural areas. But young women are effectively imprisoned in their workplace and allowed minimal contact with the outside world for up to four years.

A recent survey of 743 spinning mills across the region, carried out by the India Committee of the Netherlands, a human rights organization dedicated to improving the lives of marginalized people in south Asia, found more than half of the mills were illegally restricting the free movement of resident workers.

The director of the organization Gerard Oonk said, “Mill owners usually defend themselves on the pretext of protecting the girls from abuse far away from home, but locking young women up for years at a time is not the answer”.

The Guardian found evidence of worker confinement at premises belonging to Sulochana cotton mills, which supplies Primark, and Sri Shanmugavel mills, which feed into Primark and Debenhams’ supply chains.

On visits to spinning mills located in rural areas around Tirupur, Palladam and Dindigul in Tamil Nadu, the workers confirmed that young female workers were not allowed to leave the factory of their own free will at any time, except on rare trips to local markets accompanied by factory security.

One young woman worker of Best Corporation mill said “We are not allowed to leave the factory without wardens or whenever we want to. I work, when I am told to. I don’t complain. My family needs the money for my wedding dowry”.

According to multiple interviews with workers in factories belonging to Sri Shanmugavel mills, young women living at the factories are either not allowed mobile phones, or have their calls monitored by factory supervisors.

Local organizations said they are not allowed to check on the working or living conditions of young female workers housed at spinning mills and face intimidation and threats from factory owners.

Best Corporation acknowledged that it restricts workers’ freedom of movement outside the factory premises, because of the rural location of many of its factories. It said it has taken steps to address worker grievances, including establishing a worker committee, inviting local NGOs to train supervisors on workers’ rights, and funding an independently run telephone helpline for workers.

Neither Sri Shanmugavel nor Sulochana mills responded to requests for comment.

The UN special reporter on contemporary slavery, Urmila Bhoola, said restricting the movement of female workers had serious consequences.

Bhoola said, “They are vulnerable upon recruitment and kept in vulnerability during employment. They are also vulnerable to sexual harassment and other forms of abuse by male employees overseeing their activities during their trips outside the hostels and also at the workplace.”

The high court of Tamil Nadu has asked the state authorities to take urgent measures to address workers’ confinement.

“Restraining or confining workers to not leave mill premises of their own free will – and, when it happens, then never allowing them to move freely outside without company guarding – is clearly in conflict with Indian legislation,” said R Rochin Chandra, a legal expert and director of the Centre for Criminology and Public Policy, a research centre based in Rajasthan.

Mothercare said it has been prioritizing issues of freedom of movement since 2014 and that significant progress has been made at Best Corporation.

“We have had positive response from workers and seen a significant improvement over time,” said Amy Whidburn, Mothercare’s global head of corporate responsibility.

Next denied the problems of worker confinement existed in its supply chain.

“At no point in any of the 10 audits that Next has undertaken of Best Corporation over the past seven years has there been found to be any evidence of significant adverse impact on workers’ human rights, child labor … or any other major non-compliance.”

Tamil Nadu’s spinning mills, which feed into India’s booming export garment sector, have long been the subject of allegations of serious labor abuses, including the practice of Sumangali, where wages are withheld from lower caste and Dalit workers for years at a time.

The Ethical Trading Initiative (ETI) said international retail brands had to find more effective ways of using their influence to eradicate the potential for labor abuses in the region.

“Southern India is an exceptionally challenging and sensitive environment when it comes to improving workers’ rights, particularly the rights of young women workers,” said Martin Buttle, category leader for apparel and textiles at ETI.

“We recognize that poor conditions and restrictions on freedom of movement exist in mill-owned hostels, and a lot still needs to be done”, Buttle added.