Over the last few years, a vibrant and growing startup scene in the textiles and fashion industry has sprung up all over Europe. Jozef De Coster reports from Brussels.

Our times are fond of innovation. Many textile and apparel companies mention "innovation" in the text of their Vision and/ or Mission statements. But then, where can more daring-even disruptive-innovations be found, than in startups? This was at the heart of the European Apparel and Textile Confederation Euratex in russels on April 17-18-the First European Textile Startup Summit.

Our times are fond of innovation. Many textile and apparel companies mention "innovation" in the text of their Vision and/ or Mission statements. But then, where can more daring-even disruptive-innovations be found, than in startups? This was at the heart of the European Apparel and Textile Confederation Euratex in russels on April 17-18-the First European Textile Startup Summit.

Lutz Walter, Director of the Innovation and Skills department at Euratex, enthusiastically hailed the some-20 young starters who pitched their company at Brussels, saying: "Over recent years, a vibrant and growing startup scene in the textiles and fashion industry has sprung up all over Europe. This event will bring together this new breed of brave young textile innovators and startup entrepreneurs who bravely challenge the incumbents in this long-established industry, and open entirely new markets for textile-based products and services."

Starters, who are definitely optimistic people, are also happy people because-at least for some time-they live in an exciting present while dreaming of a great future. Most of them are not aware that nearly all innovations are either intrinsically useless or-even when useful-are never put into production (look at the fate of most of the many thousands of patents which every year are registered in the textile patent databases).

Also, most starters do not expect that their smart, well-aimed business project-when introduced in the market-will enter the inexorable world of cybernetics, where feedbacks of all kinds will force them to adapt the project, not once, but again and again. Some philosophers explain the whole sad history of mankind as an example of "cybernetics-of-the-second-order."

Opportunities abound

As Italian industrialist Paolo Canonico, president at ETP (European Technology Platform of Textile and Clothing), explained in Brussels: one can easily defend two divergent views on the current state of the European textiles and apparel industry. A pessimist will remark that in Europe this industry has shrunk into a niche industry specialising in hi-tech products which for the time being are relatively safe from attacks by Chinese and other foreign mass producers.

Since 2005, when after a period of 30 years the Multi-Fibre Arrangement (MFA) no longer adequately protected the industry, the total annual turnover of the European textiles and apparel companies has fallen by nearly 20 per cent. Many parents continue thinking that the textiles and clothing industry is a sunset industry and try dissuading their children from taking up courses in textile schools. The average age of European textile workers is increasing. Textiles and garment companies find it increasingly difficult to find employees with the right skills.

But an optimist like Canonico also looks at the bright side of the sector where he sees a lot of precious strengths partly traditional and partly newly acquired. Since 2005, the annual total value added of the European textiles and apparel companies has increased by 36 per cent. The world's top companies in fashion, luxury clothing, personal protection clothing, technical textiles, sustainable textiles, can all be found in Europe. Since 2015, employment in the sector is again on the rise and, though on a very modest scale, some previously delocalised production capacities are coming back.

But an optimist like Canonico also looks at the bright side of the sector where he sees a lot of precious strengths partly traditional and partly newly acquired. Since 2005, the annual total value added of the European textiles and apparel companies has increased by 36 per cent. The world's top companies in fashion, luxury clothing, personal protection clothing, technical textiles, sustainable textiles, can all be found in Europe. Since 2015, employment in the sector is again on the rise and, though on a very modest scale, some previously delocalised production capacities are coming back.

What Canonico likes most is that new technologies and urgent sustainability requirements create numerous opportunities. Euratex handpicked some 20 starters from the enthusiastic phalanx of innovators who are currently looking for capital, and for supporting networks that should enable them to grab their chance.

A good idea is no longer enough

Ash Mauray, author of the book Startup Lean, wrote: "We live in a fantastic time to launch a startup or a new product. And yet, most initiatives go wrong. The reason is not that we don't try hard enough, but that we waste time, money and energy to develop a product that nobody is waiting for."

So, the first question the audience at the ETP event in Brussels probably had in mind when 20 startups pitched their special idea and connected business plan was: "Is there a market for such product?" For a few years, in many countries potential investors will spontaneously add a second question: "Can this startup contribute to sustainability?" For, it is dawning even on ultraconservative Economists and financial analysts that limitless growth is a fairy tale without an happy ending.

It can't be expected hat startups, even with a big potential for sustainable growth, will succeed on their own in transforming the European textiles and apparel industry. Also, responsible authorities and conscious consumers have an important role to play. But listening to ambitious starters who are deeply convinced that they will make a difference in the sector, in and outside Europe, is an exciting experience. Let's have a closer look at three of them.

'Fashion for Good' aims at global impact

The startup Fashion for Good, launched on March 30, 2017 attracted a lot of attention at the ETP event. This startup is different from most others since it is not only built, like many others, on goodwill and creative amateurism, but funded by C&A Foundation. It boasts the support of strong partners like C&A, Adidas, Kering (with Gucci, YSL, Puma,), Zalando, Galeries Lafayette, Target.

During the first year of its existence, Fashion for Good has given several small, innovating startups a push from the back. Its core business is providing promising startups the needed expertise, contacts and resources to rapidly scale up. The ambitious ultimate goal of Fashion for Good is to pilot the global fashion sector into the circular economy.

Will this startup succeed in alleviating the very heavy ecological and social footprint of the fashion sector? Conscious clothing consumers who wonder how this sector- from fibre to fashion-is fitting in the doughnut model of the popular British economist Kate Raworth have to conclude that it does not fit at all. Its pollution and excess consumption are degrading the environment beyond repair. Millions of garment workers do not yet enjoy the comfort of a living wage and social security.

Scepsis is justified about the possible success in the medium term of Fashion for Good. Can 'fast fashion' companies be expected to voluntarily drop the core advantages of their business model (speed and low price)? Recently, even the consequently CSR-oriented (corporate social responsibility) clothing brand C&A was criticised because it presented in its Best Deals budget collection very cheap articles like t-shirts for 2 and trousers for 8. "How can C&A pretend to aspire to sustainability with such prices?", was the essence of most public reproaches. C&A explained that it requires from all its suppliers a guarantee that the workers get at least a minimum salary. Market observers remarked that C&A has to compete with price breakers like Primark.

The infinited fiber company

Another interesting startup is The Infinited Fiber Company, which was pitched in Brussels by CEO and Co-founder Petri Alava from Finland. Alava contends that Infinited Fiber is able to produce a cottonlike textile fibre from waste materials and residue biomaterials. This fibre can be recycled again and again without loss of quality. The ambition of Infinited Fiber is to replace cotton and polyester in the fashion industry and in the large market of disposable hygienic products. Also, the industry of technical products for filtration, insulation, composites, is reportedly showing growing interest.

Another interesting startup is The Infinited Fiber Company, which was pitched in Brussels by CEO and Co-founder Petri Alava from Finland. Alava contends that Infinited Fiber is able to produce a cottonlike textile fibre from waste materials and residue biomaterials. This fibre can be recycled again and again without loss of quality. The ambition of Infinited Fiber is to replace cotton and polyester in the fashion industry and in the large market of disposable hygienic products. Also, the industry of technical products for filtration, insulation, composites, is reportedly showing growing interest.

Alava doesn't want to conquer the world alone. He invites all other radical recycling innovators to cooperate with his company for building a new global ecosystem. He expects that demand will increase fast since so many big players want to get rid of the traditional, unsustainable cotton and synthetic fibres. Ikea intends to increase the use of man-made cellulosic fibres to more than 40 per cent of all fibre usage by 2030. Wrangler has the objective to replace 30 per cent of cotton in jeans. Suominen wants to bring sustainability to nonwoven markets. Tommy Hilfiger sees major potential in menswear with new fibres. Also, consumers are willing to pay a price for sustainability (or so they say), and not only in the rich countries. According to Alava, 95 per cent of the people in Brazil, China and India are actively in search of responsible products.

The Infinited Fiber Company may be a startup, but according to founders its technology is mature. It has been developed since the Nineties with more than 7 million investments. The fibres have been successfully tested in industrial production tests by an H&M subcontractor. According to Adidas, the fabric made of the fibre "has already a commercial quality."

Now, Infinited Fiber wants to attract investors for scaling up production. In 2020-21, a flagship fibre plant with a capacity of 25,000 tonne should be built, and in 2022-23 a first high volume plant of more than 100,000 tonne. "Join us, and we don't need another planet Earth," Alava is telling business angels and other potential investors.

Scalable Garment Technologies Inc

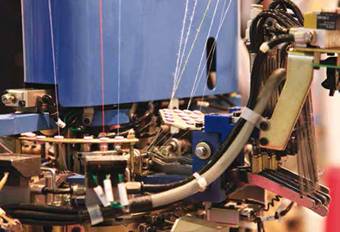

It's not difficult to detect some weak spots in the brave future plans of Fashion for Good and The Infinited Fibre Company. It's even less difficult to shoot holes in the project presentation of the three Canadians who want to change the world of fashion with their startup Scalable Garment Technologies Inc. They have designed and prototyped a robotic knitting machine to produce custom seamless knit garments in the size, material and style chosen by customers. This means better fit and less waste. The three pioneers predict a future where all mainstream clothing production is on-demand and completely manufactured by machines.

It's not difficult to detect some weak spots in the brave future plans of Fashion for Good and The Infinited Fibre Company. It's even less difficult to shoot holes in the project presentation of the three Canadians who want to change the world of fashion with their startup Scalable Garment Technologies Inc. They have designed and prototyped a robotic knitting machine to produce custom seamless knit garments in the size, material and style chosen by customers. This means better fit and less waste. The three pioneers predict a future where all mainstream clothing production is on-demand and completely manufactured by machines.

By the way, this is the kind of utopian future that is dreamt of by the American sociologist Peter Frase, who in 2016 published the book Four Futures, Life after Capitalism. If Scalable Garment Technologies would succeed on a big scale, like they intend, the double sector issue of scarce textile resources and poorly paid monotonous labour would be resolved. As for now, the Canadian software and engineering specialists who started Scalable Garment Technologies are still working on a prototype machine that makes scarves to validate and demonstrate the technology needed for on demand manufacturing of single custom garments. Their next step will be launching a machine for producing knit ties and then a machine for fully customisable foot-shaped socks.

Comments