The movement for sustainable fashion may be a cross and patch across the world, but it is sewing a pattern in the Kingdom of the Netherlands-based largely on innovation.

A few hard facts:

An average article of clothing takes 100 pairs of human hands to make. All of those people's dreams and hopes are represented in your closet.

Of the nearly 400 billion square metres of textiles produced each year, 60 billion square metres will be left on the cutting floor.

The world consumes about 80 billion new pieces of clothing every year. This is 400 per cent more than the amount we consumed just two decades ago. As new clothing comes into our lives, we also discard it at a shocking pace. (The True Cost)

In a typical wardrobe, one-third of the clothing has not been worn in one year.

Nearly 60 per cent of all clothing produced ends up being buried or in landfills within one year of being made.

According to Ellen MacArthur Foundation, the equivalent of one garbage truck of textiles is landfilled or burned every second. Textile production is a significant contributor to climate breakdown, emitting 1.2 billion tonnes of greenhouse gases annually-that's more than all international flights and maritime shipping combined. It further warns that unless the fashion industry changes its practices by 2050, it could use more than 26 per cent of the global carbon budget (which is the amount of greenhouse gases we can emit and still stay on a path to limit global warming to 2o C).

Much of these grim reminders shout out within the 110 year old historic premises of Fashion for Good-a global platform for innovation, made possible through collaboration and community, and a network of changemakers from around the world as they reimagine how fashion is designed, made, worn and reused-in the heart of Amsterdam.

Much of these grim reminders shout out within the 110 year old historic premises of Fashion for Good-a global platform for innovation, made possible through collaboration and community, and a network of changemakers from around the world as they reimagine how fashion is designed, made, worn and reused-in the heart of Amsterdam.

As the world probes and explores what more needs to be done to minimise environmental pollution wrought by the fashion industry, the most densely populated country of the European Union-the Kingdom of the Netherlands-is quietly taking a lead as it promotes and supports brands that put sustainability at the forefront.

The Dutch garment and textiles sector is a €20 billion sector offering employment to 100,000 people in the Netherlands and 60,000 people in other countries working under contract to Dutch companies. It was in July 2016 that a broad coalition of businesses and other organisations signed the Dutch IRBC Agreement on Sustainable Garments and Textile, that aims to promote safety and equality for workers and prevent pollution and animal abuse in production countries.

Fashion for Good: And it is with this goal that Fashion for Good, launched in March 2017, stitches together brands, retailers, manufacturers, suppliers, nonprofit organisations, innovators and funders through its innovation platform- Fashion for Good - Plug and Play Accelerator. Through these programmes it promises start-up innovators the expertise and access to funding they need in order to grow.

Says communications manager Anne-Ro Klevant Groen: "Our Scaling Programme supports innovations that have passed the proof-of-concept phase, with a dedicated team that offers bespoke support and access to expertise, customers and capital. Our Good Fashion Fund catalyses access to finance to shift at scale to more sustainable production methods." Fashion for Good counts a total of 18 innovators that have participated in their Scaling Programme since its inception two years ago.

Fashion for Good is now expanding to South Asia with the launch of a dedicated regional innovation programme. Leading up to the expansion, scheduled for later this year, it is calling for innovative start-ups from across South Asia with disruptive sustainability solutions applicable to the fashion supply chain. Selected innovators will showcase their solutions as part of Fashion for Good's Innovation Day to be held at the Mercedes Benz Sri Lanka Fashion Week on November 24.

Fashion for Good is now expanding to South Asia with the launch of a dedicated regional innovation programme. Leading up to the expansion, scheduled for later this year, it is calling for innovative start-ups from across South Asia with disruptive sustainability solutions applicable to the fashion supply chain. Selected innovators will showcase their solutions as part of Fashion for Good's Innovation Day to be held at the Mercedes Benz Sri Lanka Fashion Week on November 24.

Amsterdam & Partners, a not-for-profit organisation in the public-private sector, dedicated to making Amsterdam an even better place to live, work and visit, has teamed up with Fashion for Good to highlight some people and companies that are doing pathbreaking work on sustainability. Snapshots:

Sort, Recycle: Wieland Textiles A family-run business, Wieland Textiles on the outskirts of Amsterdam, is perhaps among the biggest in the business of sorting and recycling of textile waste-used clothing-through the very innovative Fibersort technology, development of which took more than a decade, along with Valvan Baling Systems. "We collect about 100,000 tonnes of waste textiles in the Netherlands. And another 100,000 remains in the grey bin with the rest," informs director-owner Hans Bon.

The used clothing that enters the Wieland facility is sold in over 40 countries, used as source material for things like cleaning cloths, or sorted by fibre composition using the Fibersort technology that allows them to be recycled into new textiles.

After the sorting, the machines compress the second-hand clothing to be resold to a lot of East European, Asian and African nations as re-wearables. "I do about 3-4 containers a week that go to African destinations where those are resold in small bales of 45-55 kg. Africa buys by the kilo and then it is sold there by the piece.

"Sorting takes a lot of energy where every garment is graded by hand, mostly by women. We want that within 10 years, every new item of clothing that is produced contains at least 20 per cent used fibre." The textiles industry needs to invest in circularity, he exhorts.

Fibersort: Fibersort could well be the world's first textiles recycling machine which uses optical sorting to sort one article per second, as compared to 7 seconds per pair of human arms. The machine can sort 15 different materials, colour and structure (woven or knitted), and once the extension is completed it will be able to do 45 articles, which on further development will be able to double this number. "Fibersort opens the way for a circular revolution in the textiles industry: a costefficient recovery of high-quality raw materials from discarded clothing for the production of new clothing," Bon says, adding, "with Fibersort, more than 170,000 tonnes of discarded clothing can be brought back into the cycle every year as a highquality raw material for new clothing!"

Wieland which has its tagline, First in Second Hand Clothing, is now working with Valvan and various other leaders in the textiles industry on the development of a new manufacturing industry based on raw materials from discarded textile. For this purpose, these frontrunners are building a network of motivated partners who are active in the production and recycling of textiles. They do this in the context of the Interreg North-West Europe project 'Fibersort: closing the loop in the textiles industry'. "Together we wish to form the links of the zipper that seamlessly connect the ends of linear textile chains to a sustainable, circular textile economy," says Bon.

Wieland which has its tagline, First in Second Hand Clothing, is now working with Valvan and various other leaders in the textiles industry on the development of a new manufacturing industry based on raw materials from discarded textile. For this purpose, these frontrunners are building a network of motivated partners who are active in the production and recycling of textiles. They do this in the context of the Interreg North-West Europe project 'Fibersort: closing the loop in the textiles industry'. "Together we wish to form the links of the zipper that seamlessly connect the ends of linear textile chains to a sustainable, circular textile economy," says Bon.

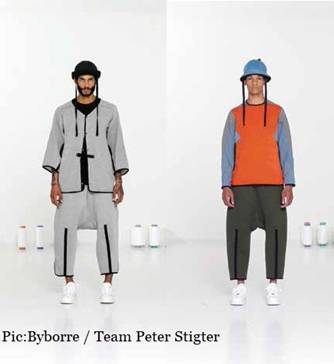

Materials & Innovation: Byborre Why this? Why that? Why? Are perennial interrogators that question 34-year-old Borre Akkersdijk's incisive mind and that led him to craft fashion clothing from a machine used to knit mattress textiles! "I think I never grew beyond a four-year-old who is always questioning, and I still do that! When I was at the Eindhoven Design Academy I was always focusing on materials. I was introduced to a factory that was making mattress textiles. I was intrigued and said I want to use this machinery for fashion. I was told it will not be possible, but I questioned that and within a couple of weeks I rewrote their programmes and got fashion clothing out of their machines. That's the base we are building on now. Over time as I challenged the machines more and more, every time I saw new opportunities. The focus of my studio is textile from the core-we develop textiles from the yarn to the end product. Now with a company and team of more than 22, we need to focus more."

This textile designer machinist professes that he "loves to create" and in doing so a big chunk of the effort goes in bridging the communication gap between the machine and the designer. No easy task that, but for Akkersdijk it is as simple as answering a question.

This textile designer machinist professes that he "loves to create" and in doing so a big chunk of the effort goes in bridging the communication gap between the machine and the designer. No easy task that, but for Akkersdijk it is as simple as answering a question.

"The language of the machine is very different from that of a designer. We develop internal software to help bridge that language. It really is a tool of our textile development kit (TDK) for other brands so that they can design in the illustrator and we transfer it to the machines. That's one of the biggest challenges. As a designer I would come to a machine technician and say this is what I have in mind, and he'd say can you write the computer program. We are focusing on this too and developing for the future. We want to push these boundaries.

"The dialogues we create thus internally is also an example of how we wish to scale up later in production. The direct link that we have to the software and hardware of the various machinery brands is a monthly interaction where we discuss about the pros and cons of each and even put the machines from different brands next to each other-so that they can see what each machine is doing and how theirs is faster, slower or whatever, as compared to the other. In terms of the products we make, what I made in 2011 beginning is still relevant today after 17 fashion seasons or more, not because it is fashion related but material and shape-related. That's something we always try to keep in our DNA-that the focus is always textiles and material, where shape can give function. The effort also is to push the machine to give us more and more where we can enhance textiles from being textile on the metre to selling engineered patterned pieces.

"When you develop something functional and good, you will keep it. And a lot of the things that we develop are picked up by other brands rapidly. Three seasons ago, we did on-pattern development with different functionalities on both sides for top cyclist brand Rapha and they translated that into their own designs. They used our design philosophy-the building blocks on how to make a design, how to choose functionality in the yarn and where we could scale it up. It was a textile development kit for them. It is also how I foresee the future and continue to help brands. We make it so easy for them that they do not have to think of development. Brands have neither innovation budgets nor time. And therefore, we deliver production facilities and help them to produce and scale up."

"At Byborre we make the right amount of textiles for the right people at the right price. The moment companies see a textile that has design and function, they buy it not just as a consumer of textiles, but as part of their storytelling, as a marketing strategy," he affirms with quiet confidence.

And that his products command the price they ask is reflected in Byborre's half a million euro turnover on innovation-and this only for the last season!

And that his products command the price they ask is reflected in Byborre's half a million euro turnover on innovation-and this only for the last season!

Byborre has its own fashion label to showcase what it can do. It may be designing primarily for men but about 20 per cent of its product line is sold to women. "More than half of the stores we sell to is in Japan because it is all material and quality focused. We are retailing through 40 doors in Japan, and also sell our innovations to that country."

On problems encountered early on in his career, Akkersdijk reflects, "When I was developing for the likes of Louis Vuitton, Moncler, Nike, and at this moment Adidas, we realised that I was the middle man-between the fibre and the yarn, between the yarn and the textile, and the textile and the product-I had a vision for myself and for the client on who the end-consumer was, and why I was building that product. But in the beginning, I could not go into the supply chain. The closest I got to it was at Premiere Vision where we had no knowledge of what all the factories were doing. We now have the first mover advantage on our innovations and our testing platform."

Byborre has embraced an open source mentality, allowing others to create their own textiles using the studio's signature techniques, and calling these projects.

Byborre Inside. They work across companies to benefit the entire knitting industry. Additionally, through their Byborre Inside and TDK initiatives they are truly opening up the textile making process, allowing others access to their pioneering fabrics and research and offering them the chance to create, collaborate and rethink. This sharing of expertise and textiles puts the planet ahead of profits.

"You are not going to hear me say the word sustainable too often. This is because, to be honest, it should be a no-brainer. All the yarns, all the cottons that we use, we make sure that we go to the factories so that they can tell us where the fibres are from, their functionalities, and they understand our way of working. If we sell in Europe on a bigger scale, we want to get the materials from Europe, we want to build the textiles in Europe. That's something we are also setting up for the bigger brands. In the end we work from the material and innovation. I believe we work with the focus on innovation and create a better product that will last longer and will help the end consumer to respect that much more as they will know where it is coming from. A lot of products you will see from us is also about educating the end consumer not just about the aesthetic of the product but also explaining what that aesthetic does for you, why the material is better. And maybe even take a part of it and get the client to ask for more sustainable yarns."

"You are not going to hear me say the word sustainable too often. This is because, to be honest, it should be a no-brainer. All the yarns, all the cottons that we use, we make sure that we go to the factories so that they can tell us where the fibres are from, their functionalities, and they understand our way of working. If we sell in Europe on a bigger scale, we want to get the materials from Europe, we want to build the textiles in Europe. That's something we are also setting up for the bigger brands. In the end we work from the material and innovation. I believe we work with the focus on innovation and create a better product that will last longer and will help the end consumer to respect that much more as they will know where it is coming from. A lot of products you will see from us is also about educating the end consumer not just about the aesthetic of the product but also explaining what that aesthetic does for you, why the material is better. And maybe even take a part of it and get the client to ask for more sustainable yarns."

The journey has not been easy. Akkersdijk remembers how the "perfect showcase was at the Paris Fashion Week where we sold to the most high-end boutiques. Until we saw top athletes walking down the ramp, we were questioned by every big brand. All we heard was, "It is nice that you make these crazy textiles, but those don't work for my brand." That's when we decided to make our own brand to prove that what we have created is very interesting. Moncler, now shut down, was one of the few naysayers but research and sampling with the brand is still on at the Byborre atelier.

RB: Here we are talking about sustainable fashion and we know that fast fashion is almost an epidemic of sorts. People are into fast fashion-the younger lot-and then you are saying that the products that come out of your place would be twice or thrice priced more than the normal one. How do you balance this out saying that fast fashion is cheap, read-to-wear, easy-tothrow while sustainable fashion is something that will last. How do you strike a balance and how do you get the younger customer, who is the customer of the future, to buy into your theory, your concept of sustainable fashion?

BA: I think, if I would do only for my own label, I would not make that much of an impact. Yes, it is very interesting, and the design directors are wearing them, and we even sell a few hundred pieces. If you talk about what the problem is about fast fashion and specially now with more and more people buying it, it is just the lack of understanding. Even if we try to educate them with movies, that doesn't work because there is no feeling invested in the thought. The right approach would be to enable the youth to be the heroes of tomorrow. The moment you give them knowledge, make that 'sustainable' product, make it cool and make it tell a story, then there is no reason why it should not impact them.

I think the best example that switched the world was the whole straw story a couple of months back. Suddenly everybody in sustainability knew the story of the straw, like what was the problem that it was posing. In Bali, there is no straw at all anymore because suddenly people felt deep about the subject and there was a change in the mindset. How many of us know where the fibres of the clothes that we are wearing come from? It is not because you don't want to know but it is just that you didn't get the opportunity and there was not a clothing piece with all that information. This is something that I am pushing very hard in my work.

Talking about the future, Akkersdijk states, "In the last decade sportswear made giant strides into our wardrobes as more functional pieces of clothing. If clothing becomes more functional, you will probably wear less different things. Think the big clunky mobile phone when it had just come into the market and the homogeneity now in terms of design and functionality. And then haptic feedback will be a new language. We are working on it. The biggest organ is the skin. We can understand things better when we touch or feel it."

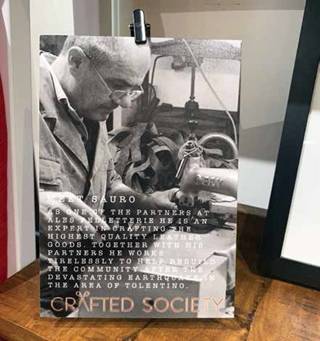

Artisans and Heritage Skills: Crafted Society

Like in any other part of the world, the crafts they encountered were in danger of dying out. The youngest apprentice they met was into her fifties, and this husbandwife duo was looking for just the right opportunity to launch their business. With a cumulative work experience of more than 35 years in fashion/footwear/luxury, looking after operations in Europe, Middle East and Africa, Martin Johnston (founder and co-pilot) decided to hang his boots (2015) and with his beautiful and creative wife Lisa Bonnet-co-founder and creative director-embarked to resolve the biggest problem they could identify as they travelled through the Italian Tuscany and Marche regions looking for artisans who could craft for them beautiful objects, be it clothing, footwear, home fashion, liquor or what have you.

Like in any other part of the world, the crafts they encountered were in danger of dying out. The youngest apprentice they met was into her fifties, and this husbandwife duo was looking for just the right opportunity to launch their business. With a cumulative work experience of more than 35 years in fashion/footwear/luxury, looking after operations in Europe, Middle East and Africa, Martin Johnston (founder and co-pilot) decided to hang his boots (2015) and with his beautiful and creative wife Lisa Bonnet-co-founder and creative director-embarked to resolve the biggest problem they could identify as they travelled through the Italian Tuscany and Marche regions looking for artisans who could craft for them beautiful objects, be it clothing, footwear, home fashion, liquor or what have you.

"We started from this kitchen table and we knew exactly what we wanted to make-beautiful shoes, bags. I had always wanted to start my own brand. Lisa has a very stylish eye. We knew we had to make it in Italy. And that's when we hit our first roadblock. Nobody tells you who the crafts people are. I called up some friends in Italy and told them our concept and they told us to come to Italy and we started visiting big factories of big organisations. We wanted to know who the artisans were, their families, how long the craft had been in the family circle and what their biggest challenges were. And we ended up meeting 5-6 craftspeople and there was a red thread running through them all. They didn't know one another, and their biggest challenge was the identification of the next generation to come in and learn what their fathers and forefathers had taught them.

"We were driving from one artisan factory in Tuscany to another in Marche and I told Lisa we need to preserve the crafted society and Lisa exclaimed-this is it, this is what we will name our brand, and thus Crafted Society was born and christened. As a first step, we went back to these artisans and told them we want to help you- we want your name on the product. The artisans were surprised as no one had done this before. We realised it is time to think different and do it. Our footwear technician from the Marche region, Enrico Pessalachia, told us we can get our shoe boxes, tissue paper and all the components of the shoes within a 12 km area. This, we felt, was more impactful as we could then sustain multiple artisans and even local communities and that the idea could apply to different product categories-we had embarked on our journey!"

Finding roots: Sustainable fashion is a hot topic, but when Crafted Society started, says Bonnet, co-founder and creative director, terms like sustainability, ethics, social responsibility were just about brewing in the board rooms. "Therefore, we decided that as a new brand we needed to pull out all stops and go even a step further. Not only do we have social responsibility and all its concomitants, we decided to adopt a transparent modus operandi. By being transparent in terms of who makes our products-our primary producers of our finished goods suppliers, we also identified who were the component manufacturers or our secondary suppliers, and then the tertiary suppliers that almost no one talks about-where the raw materials come from."

Finding roots: Sustainable fashion is a hot topic, but when Crafted Society started, says Bonnet, co-founder and creative director, terms like sustainability, ethics, social responsibility were just about brewing in the board rooms. "Therefore, we decided that as a new brand we needed to pull out all stops and go even a step further. Not only do we have social responsibility and all its concomitants, we decided to adopt a transparent modus operandi. By being transparent in terms of who makes our products-our primary producers of our finished goods suppliers, we also identified who were the component manufacturers or our secondary suppliers, and then the tertiary suppliers that almost no one talks about-where the raw materials come from."

Why Italy I ask, even though I quite know the answer. "We have had a deep love for this country for many years, and of course we recognise that when the hundred per cent made-in-Italy stamp is applied to a product it is a monologue between a brand and the end-consumer. And we wanted to create a dialogue. To back our power play we decided to promote every single artisan within the chain. So, we have the cardboard box maker, tissue paper artisan, the zip pullers, the buttons, insoles- everyone gets a platform through Crafted Society. Ultimately whether they make finished goods or they are a tannery or they are making a tie-dye organic cotton canvas, we believe that by promoting these people to the greater world more and more businesses can find more such people and hopefully that's the way the crafts can be preserved for the next generation. In Holland we have a sustainable crafted gin, a sustainable coffee brand, tea and lots more."

RB: Are all the crafts people from Italy?

MJ: Yes, they are. Our primary suppliers are the finished goods artisans, our secondary suppliers are for components (think packaging, laces, hardware for bags, buttons) and our tertiary suppliers are for raw materials. We name and platform all of them online under Luxury for Good/ sustainability. Shoes-finished goods (IFG, Mirage Calzature and Laboratorio Artigiani Torresi); Hats-finished goods (Sorbatti); Bags & small leather goods (Ales Pelletterie); Cashmere (Lanificio Arca); Jeans (Laboratorio IMJIT35020)

RB: How many craftspersons in fashion and how many in other streams is the Crafted Society working with currently?

LB: Across primary, secondary, tertiary suppliers we work with more than 100 artisans.

RB: How do you split the sales from your shop with a craftsperson?

LB: We pay the asking price for the products from our artisans. We don't ask for any discounts and their prices to us includes their own profit margin. We mark up three times cost price (traditional luxury houses markup cost price x 8-12) which also includes tax. We make our 1 per cent donation from global sales out of our own margin.

RB: What new and what's lined up for the future?

MJ: We have just launched a new homewear product category which has got off to a great start. We launched two cashmere throws. One is completely upcycled from leftover cashmere yarn which would otherwise be waste-the throw is 1.8m x 1.4m and includes 365 individual colours-one for every day of the year. It is named after one of Lanificio Arca's longest serving artisan- Albertina. The other cashmere throw is 70 per cent recycled cashmere, 30 per cent wool. From a business perspective we will launch our first international partnership in August 2019 in Canada.

Through a recently brokered deal, we will work in partnership to physically bring Crafted Society and our fitting room concept to our first market outside of the Netherlands. We will also be launching two new partnerships with finished goods shoemakers-Mirage Calzature Italia (based in Marche) and Laboratorio Artigiano Torresi (Marche)-to help us fulfil our growing sneaker business. Later this year, we will be adding more products within our bags, shoes and homewear offerings. We hope that in the near future we can set up our own foundation and work with our craftspeople, do scholarships and apprenticeship for the next generation and help keep the crafts alive and thriving. Crafted Society operates from a 300 sq ft store in the heart of Amsterdam city.

Sustainably affordable: Unrecorded

Sustainability should be a no-brainer and definitely not in your face, according to Jolle van der Mast and Daniel Archutowski-the founder duo of Unrecorded. The two felt there was a need for high quality sustainable basics without any compromise on style.

"We want to inspire not only the people who are interested in sustainable clothing but even those who are not. If we can reach those people, our impact will be much bigger," asserts der Mast, who holds a Masters degree in Business & Engineering. It helped that he had a corporate background working in the coir industry and industrial packaging where he got into touch with textiles and then ran a textile fabric factory in the UK. Archutowski was a graphic design-art director with a marketing career in the clothing industry with the likes of Tommy Hilfiger and Calvin Klein for 14 years.

The little over two-year-old brand, Unrecorded has done well to open three stores (total area: 1,330 sq ft ), and receive two rounds of investments. "We have a number of angel investors on board including a founder of a unicorn from Vancouver. Our last funding round included the largest and oldest impact investor in the Netherlands, Doen. Over 25 years, Doen has been the largest investor in sustainable and social start-ups."

The little over two-year-old brand, Unrecorded has done well to open three stores (total area: 1,330 sq ft ), and receive two rounds of investments. "We have a number of angel investors on board including a founder of a unicorn from Vancouver. Our last funding round included the largest and oldest impact investor in the Netherlands, Doen. Over 25 years, Doen has been the largest investor in sustainable and social start-ups."

Explaining the name Unrecorded, der Mast says, "It comes from the fact that something that is unrecorded is 'live' and therefore 'real'. It has elements which are unpolished, but it is those elements that give something its character. We believe many things in the fashion industry are so polished that it has become fake. This is also one of the reasons we share pictures and videos of production facilities. A factory that is well managed is a beautiful place where great things are made by people. Many brands in the industry hide this element, understandably, because they are often not proud of where their garments are made and don't want people to look further than their curated billboard.

"Two years back when I met my co-founder Daniel, we both saw a gap in the market where there were a lot of sustainable brands which are high-end and many others often high priced. He did not like the way the speed in the fashion industry kept on increasing and not just at the expense of the quality of the product, but also the quality of the content.

"We believed that in the current market scenario where it is easy to communicate with people worldwide, we wanted to set up a direct consumer brand where everything is as sustainable as possible but doesn't have the aura of a sustainable brand. We did not wish to communicate sustainability as our first communication, but everything we do, we think sustainability and our model is-from materials to manufacturing to marketing everything is single material fabric-we use hundred per cent cotton and wool. No blends, no polyester. We use GOTS-certified organic cotton. We also develop all our fabrics with the mills in Portugal, while the wool yarns come from Italy. All our manufacturing is in Portugal, and only the scarves from Italy.

Design: We of course do our own designing. I am from an engineering background, and my business partner comes from a background in clothing. Initially, we got a network of designers to assist us. Now we use a lot of reference products which are readily available, make technical specifications, then protos, and then you see what and where you want to change.

Collections: We don't do collections. Everything we do is never out of stock. Every item has the basic white, blue and oxfords. We will soon launch bottomwears. While the shorts will be in stores shortly, the chinos will be on shelves by September.

Target audience: In terms of the target audience, it is not about either men or women. We never talk about sex. We are unisex. We sell to everyone. Most of our XL oxford shirts go to women. All our larger sweaters and wool sweaters go to women. Our collection is for everyone. Sometime down the line we may come up with specific styles for women.

Sells: We sell through the internet, ship directly, and our two stores in Amsterdam, where the focus is on currently. We share our cost base; so, our prices are half the price in comparable quality. And we never go on sale.

ROI: We are yet to break even and hope to do so in the next 12 months."

Click here for the complete article.

Comments