The sportswear segment could well be the first to resurrect itself after the current crisis. The segment has everything going in its favour—especially history and science.

It’s a difficult time for forecasters. The covid-19 pandemic, geopolitical tensions and rising protectionism, as well as the global economic recession and unrest in several countries are creating much uncertainty. As always, some Black Swans are lurking somewhere in the dark. And yet, expecting a bright future in the medium term for the sportswear sector is not that foolish, even in India.

An important argument is that rational optimism urges us to believe that after the corona dip, the human development index (HDI) will continue rising. The evolution of human development may be more relevant for the sportswear business than the the holy cow of annual GDP growth. Thanks to people-oriented economists ith global intellectual influence, like the Pakistani economist Mahbub ul Haq and his close friend the Indian Nobel Prize winner Amartya Sen, the HDI is also nowadays a respected tool for comparing the performance of countries.

Is there a more attractive symbol of human development than sportswear? Admittedly, the use or consumption per capita of sportswear in the countries compared (189 countries in 2019) is not statistically measured by the HDI. But it seems reasonable to expect that global expenses per capita for sportswear will continue rising as long as the key dimensions of the HDI are showing growth.

Every person who puts on a sports shirt and running shoes is actually telling:

I invest in a long and healthy life, I have access to education, and I enjoy a decent standard of living. These are precisely the three key dimensions of the HDI.

Reason and Science

Can one be sure that this index will continue rising? Some forecasters pose as if they are at home in Einstein’s four-dimensional universe where the past, present and future are one. For a hefty fee, they tell governments and companies, without much hesitation, what the future has in store. Often, their detailed predictions appear afterwards to have been biased and wrong, like those of ordinary mortals. Instead of relying totally on the advice of half-blind futurologists, it’s wiser to do some independent thinking based on statistical and other data. That’s what the Canadian-American cognitive scientist Steven Pinker did when he wrote the book Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress (2018).

If you agree with Pinker’s analysis and conclusions, you’ll probably admit that the HDI and connected phenomenons like the consumption of sportswear will continue growing. It’s indeed quite likely that people will spend more active time on sports in order to improve their health (also to survive the next pandemic) and to enjoy life in agreeable connection with others. Especially, outdoor sports could benefit from the current pandemic. On June 8, the European Outdoor Group (EOG) released details of new research which reveals that the appeal of outdoor activities has been boosted by enforced covid-19 restrictions. In a survey of consumers in seven countries, 70 per cent of respondents stated that they are specifically looking forward to participating in outdoor activities.

The Big and the Bold

According to the market researchers of Statista, the American company Nike with a turnover in the fiscal year 2019 of $39 billion is the world’s largest producer of sportswear / sporting goods. The steady runner-up is Adidas with a turnover in 2018 of $25 billion, trailed by VF Corporation, Puma, Under Armour and Asics. Other popular brands include Columbia Sportswear, Fila, Umbro, Reebok, Li Ning, Patagonia, Lacoste, Kappa, Lululemon Athletica, among others. Nike is as well the global number one in terms of financial profits. According to the McKinsey report The State of Fashion 2020, the profits of Nike amounted to $3 billion in 2018 compared to $1 billion for Adidas (Germany), $861 million for VF Corporation (USA), $532 million for Anta Sports (China) and $400 million for Lululemon (Canada).

In 2018, all sportswear brands together fished worldwide $174 billion out of the pockets of eager-to-move consumers. Also according to Statista, the Indian sportswear market was valued at over ₹540 billion in 2018 across the country, almost ₹100 billion more than the previous year. An overall exponential rise in the market value of sports apparel and footwear has been witnessed in India over the years since 2015.

Posing as a fortune teller, Allied Market Research said they expected that sportswear sector turnover would rise to $184.6 billion in 2020. They could not know of course that in the first months of 2020 the covid-19 outbreak would expand into a pandemic. But even if they had known, they would not have been able to predict the impact of the coronavirus on sportswear production, distribution and consumption.

Great Sector

Not very long ago, sectors which excelled in growth and profitability, like ‘big oil’, ‘big pharma’, ‘big food’, ‘big finance’, were celebrated as ‘great sectors’, regardless of their positive or negative contribution to the people and planet. Today, business analysts tend to pay a bit less attention to accounting results and a bit more to social and ecological performance. It looks as if today the sportswear subsector gets more ‘likes’ than other subsectors of the textiles and clothing industry, with the notable exception of medical clothing. The reason could be that on the whole sportswear is recognised as being more consciously produced and consumed than other apparel products. Also, sportwear brands tend to profile themselves as more courageous and enlightened than other brands.

This should not be a surprise. Sportwear brands which want to communicate with their final customers know that they’ll be talking with people who on average live (and thus probably also think) more consciously and intensely than most other people.

‘Woke’ Brands

People who regularly practice sports not only enhance their bodily fitness but as well their creativity (jogging and cycling are competing with the daily shaving session as sources of creative ideas). It is supposed that especially endurance sports also stimulate independent thinking, as Alan Sillitoe hinted in The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner. Anyway, brands who engage in communication with sporting people are aware that they are not talking to couch potatoes but to ‘woke’ people.

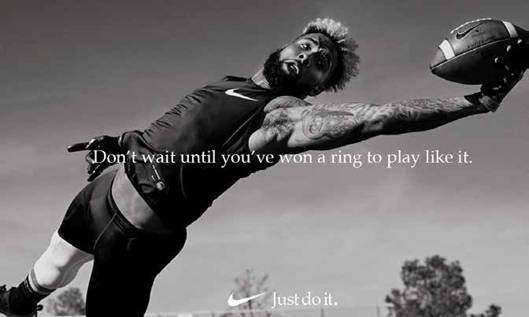

Sector leader Nike took a calculated risk when choosing in 2018 the NFL-player Colin Kaepernick as the face of a new promotion campaign. Kaepernick was in 2016 the first player who, to the anger of Donald Trump and likeminded people, kneeled during the playing of the national hymn, as a silent protest against police violence and racism in the US. At the end of May 2020, Nike again took the lead by promptly reacting against the scandalous murdering of George Floyd, the black citizen who in Minneapolis died under a police knee. The shoe and sportswear brand, worldwide known for its ‘Just do It’ slogan, launched the striking advertisement ‘For once, don’t do it’. Competitor Adidas immediately joined in. The brutal police intervention in Minneapolis (Minnesota) reminded people that Main Street (1920), in which Nobel Prize winner Sinclair Lewis satirised the narrow-mindedness of small town America was situated in Minnesota.

On the covid-19 Tracker of the Worker Rights Consortium (‘Which brands are acting responsibly toward suppliers and workers?), by the end of June one could find the names of leading sportswear companies like Adidas, Lululemon, Nike, Under Armour, VF Corporation, among those who had committed to pay in full for orders completed and in production. Surprisingly, GAP was not yet on this list. One of the six primary divisions of GAP is Athleta, an athletic-wear brand for women.

Suing the President

Sportwear brands like Patagonia, Nike, Adidas, Asics try eagerly to convince consumers that they are brands for which ecological sustainability is of paramount importance. It’s of course difficult to judge if they really deserve their green image. How to make a distinction between green image-building and real performance? One is never sure, but knowing that it’s easier to control companies which sell material things than organisations and professionals who only produce words, it seems reasonable to accept as true what brands are telling about themselves, as long as they don’t spark angry protests from specialised NGOs and / or other organisations.

An example. On the website of the Californian outdoor clothing and gear brand Patagonia, one can read that since 1985 Patagonia donates at least 1 per cent of its turnover to environmental action groups (in 2019, Patagonia’s turnover was around $800 million). Patagonia also proudly states: “We are in business to save our home planet. From supporting youth fighting against oil drilling to suing the president, we take action on the most pressing environmental issues facing our world.”

Good on You

That’s fine, but how does for example the well-known Australian organization ‘Good on You’ judge Patagonia? ‘Good on You’ is specialising in sustainable and ethical brand rating. It recently came in the news because its high profile supporter Number One, the British actor and ethical fashion champion Emma Watson, on June 16 joined the board of directors of French luxury fashion conglomerate Kering (including Gucci, Saint Laurent, Balenciaga, Alexander McQueen).

In September 2019, ‘Good on You’ wrote: “We’ve given Patagonia an overall rating of ‘Good’, based on our own research. This brand lives up to the standards it set itself by pushing for sustainability across the board. Patagonia is taking impressive action to reduce its environmental impact. It is leading the way when it comes to labour policies. It received the second highest rating in the 2019 Ethical Fashion Report (the sixth such report published by Baptist World Aid), which looks at the payment of a living wage, transparency, and worker empowerment. Patagonia has also strong animal welfare policies.”

Companies that get a better than ‘Good’ rating from ‘Good on You’ are very rare. According to a June 2020 report, the German sportswear brand Bleed is in all aspects a ‘Great’ brand. It uses a high proportion of eco-friendly materials. It ensures payment of a living wage in most of its supply chain. Also its animal rating is ‘great’. Bleed states that its entire product range is vegan. Bleed is a small company; its size makes it probably easier than for big companies to score exceptionally high.

Not Perfect

Nothing is perfect in an unperfect world. This rule also applies to the standard bearers of the sportswear sector. The composition of the boards of directors of sportswear sector leader Nike and other famous American companies which after the George Floyd murder touted their support for the ‘Black Lives Matter’ protests, was examined and sharply criticised. In the opinion of many black Americans, the examination resulted in an unmasking: most of the supporting companies had zero or only one black director in their board. Nike itself has acknowledged that its executive ranks aren’t as diverse as they should be. While about 22 per cent of all Nike employees are black, the proportion shrinks as you move up the corporate ladder. When you get to the level of vice-presidents, 10 per cent are black and 77 per cent are white. Nike was also forced to change its pregnancy policy for female athletes under pressure of top runners like six-time Olympic champion and Nike runner Allyson Felix.

Nowadays the apparel industry, including the sportswear segment, is mostly under fire because of its ecological and social underperformance. Inevitably in the future more aspects of the industry will be scrutinised and criticised. How should sportswear brands protect themselves against the claim of the Scottish psychiatrist RD Laing that “parental love” is often a form of violence? Should companies continue conspiring with parents in order to lure very young children as early as possible in the tough world of competition and heroism?

Some Speculations

It’s very likely that contact sports like wrestling and tribune sports like soccer or horse racing will get severe blows due to obligatory covid-19 adaptations. As for the consequences of corona on outdoor sports, the future is difficult to foresee. Let’s nevertheless indulge in some speculations:

-

It can be expected that the corona future shock combinedwith increasing climate-awareness, will result in less per capita consumptionof sportswear, but increasing interest for sustainably made high-quality itemswhich can be used for a longer time.

-

Though hopefully more people will make more rationalpurchasing choices, it’s an illusion to believe that suddenly the choices ofsportswear consumers will be exempt of ‘conspicuous consumption’ (term coinedby the American economist Thorstein Veblen) and mimetic desire (see the Frenchsocial scientist Rene Girard). When the elegant Belgian crown princessElisabeth on May 20 appeared in some newspapers wearing jogging trousers of thesportswear brand RectoVerso, the next day sales of the brand doubled.

-

For many consumers, sportswear will continue playing animportant role in what the American cultural anthropologist Ernest Beckercalled a ‘symbolic pillar of self-esteem’ (The Denial of Death, 1973). So,brands will continue inventing bold slogans and designing attractive productsthat help support the myth that practicing sports is the fountain of youth.

-

The ‘acceleration of history’ as the Israeli historian YuvalNoah Harari called the effect of corona in March 2020 will probably give anedge to the biggest and the richest sportswear brands. Their survival chanceslook better than those of their small competitors. Again, the winners will takeit all. Many small and medium-sized companies will disappear or will be takenover by larger ones.

-

The traditional national sports preferences, like Indiapreferring cricket, US being fascinated by American football and Brazil goingmad for soccer, will continue existing.

-

Market differentiation will even become more important thanin the past, with brands luring ever more women and children to the sportfields.

Brands will also continue trying to convert more casual sporters into sportfreaks. Casual runners tend to follow the example of simplicity given by the Mexican Tarahumara long distance runners. Runners of this Indian tribe easily run 160 km over mountain and valley in simple clothing and with selfmade shoes. Sportfreaks, on the contrary, tend to listen to world-class runners like Meb Keflezighi, an American, who most of his career was sponsored by Nike. In his book 26 Marathons (2019), Keflizighi explains how “wardrobe mishaps,” a poor choice of shoes and outfit, can cost athletes a victory and even their career. It’s clear that freaks like Keflezighi will always spend a lot more money to sportswear than their more moderate competitors.

This article was first published in the July 2020 edition of the print magazine.

Comments