Renewed surge of coronavirus infections in China have created disruptions in working of the Chinese ports, leading to high waiting times for shippers and continued rally for container prices. With global demand growth being much more robust than supply, trade growth prospects look slim, and trade forecasts are likely to be revised downward.

Challenges to global trade recovery is expected to prevail for long, as COVID-19 infections rise on the Yantian port in China. Guandong province in China saw 22 new coronavirus cases on June 7, 2021 and authorities have put in place certain restrictions on movement. The restrictions have resulted in delays as long as 14 days on major ports of Yantian, Shekou and Nansha in the southern parts of China. Huge backlog on the largest ports in the world, have increased delays in schedules of shipping companies and led to the rally in container prices to continue. Global demand continues to increase, with online commerce booming, while supply-side languishes.

Drewry's composite World Container Index continues to rise as shipping costs soar due to tremendous delays. The composite index indicating price for a 40-ft container, rose to USD 6,957.4 as of week ending June 17, rising 3.4 per cent over a week, 13.4 per cent over a month and 405.7 per cent over a year. Container price on Shanghai-Rotterdam route was the highest ever at USD 11,196, rising 6.4 per cent in a week, as there is a huge demand to ship goods out of Chinese ports to Europe and the US. Prices on Shanghai-Los Angeles route saw slight easing on pressure rising by just 1 per cent over last week to USD 6,358 as of June 17. This comes as a relief as throughput on the Los Angeles port improved in May-21. However, the rates are still 197 per cent higher than last year. Container prices between Rotterdam and New York rose the fastest between June 17 and previous week, solely due to a rise in import demand in both EU and the US. Volume of loaded imports on the Los Angeles port increased to 535,714.2 TEUs (Twenty Foot Equivalent Units) in May from 490,126.9 TEUs in April, indicating relaxation in congestion on port. Empty container exported from the Los Angeles port also rose by 7.0 per cent m/m in May, highlighting the extent of demand for empty containers on the Chinese ports.

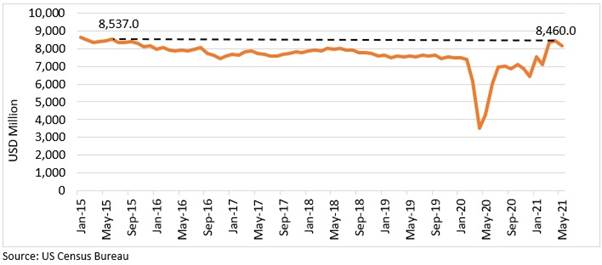

This has largely to do with much faster demand recovery in the US than expected, while coronavirus infections continued to impact supply chains. As an example of this demand, retail sales of electronic appliances in stores boomed this year, and sales in Mar-21 surpassed all monthly figures in almost the last six years. Now, as semi-conductor shortage intensifies and container prices rise, prices of electronic appliances will also likely increase, and volumes are expected to dip.

Figure 1: Sales of electronic appliances stores in the US

Major blow to exporters

This could be a major blow for small exporters for whom the logistics costs could be a crucial factor when deciding about whether, or not, to trade. UNCTAD's data on maritime costs shows that the cost of shipping a commodity from China to the US could go as high as 42.2 per cent of the FOB value and the average is at 2.8 per cent of FOB for all commodities transported. Even at 20 per cent transport cost to FOB ratio, a doubling of shipping costs would mean an additional 20 per cent cost on the product. A 13.3 per cent rise in a month could eat up the entire margin of exporters when prices of goods are very sticky and can't be adjusted in such a short period of time.

Higher costs translate to either lower profits for the sellers, or passing the costs to consumers fully, or not trading at all. In any case, at a time when the peak demand season (Aug-Oct) is near the corner, supply delays will only mean loss of sales for many exporters who aren't able to meet the huge logistics costs. This would further strain many industries where firms have only slowly started to increase production and are largely dependent on exports to the developed world.

Reasons for spike in container prices

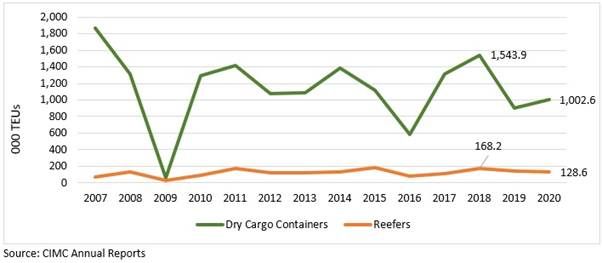

The shortage in containers is not a result of the pandemic but was in the making for at least the last decade, if not more. Post the Global Financial Crisis in 2008-09, global trade growth has remained subdued, along with growth in global GDP. Global supply of container boxes has remained stagnant over the decade, in the wake of lower expected activity in global trade. Container sales volume of the largest manufacturer in the world suggests just that. China International Marine Containers Ltd (CIMC) is the largest manufacturer of cargo containers, and its sales of both dry cargo containers and refrigerated containers has not grown much over the years (Figure 2), and even plummeted intermittently. As per CIMC's annual reports, the sharp drop in dry cargo containers sales in 2019 was due to "the influence of trade frictions in 2018", which led to a decline in demand of new containers.

However, this is just one part of the story. A slightly more nuanced outlook on the container supply relates to market concentration in the industry. The industry is highly concentrated with 90 per cent of supply coming out of China and CIMC holding 40 per cent share. Container prices falling from 2014 to 2016 led to a huge burden on margins of these companies, leading to combined production cuts by Chinese firms. Similar production cuts were seen in 2019 as well, as revenues of shipping companies fell. CIMC's revenue fell close to RMB 8.0 billion between 2018 and 2019. Come 2020, as global trade flows dried up, container manufacturers in China maintained lower production to keep prices stable. The recovery in production from there on has been marginal relative to the supply requirements.

Figure 2: Container sales volumes of CIMC

Another aspect of rising logistics price is a mismatch of container allocation and demand. Increased blank sailings last year led to containers getting piled up at major ports in the US, creating container shortage at the Chinese ports later-on. With port congestions and shippers running late on schedule, cancelled sailings have again started to increase. This is expected to aggravate the current shortage of containers at the Chinese ports and will likely keep the prices rising.

Air cargo costs rise

Air cargo prices also continue their historic rise, as demand for overseas transport gallops and trade volumes shifts from ocean to air. Major trade routes CN/HK-US, CN/HK-EU, EU-US and US-EU have seen air cargo prices rise in May by 151 per cent, 84 per cent, 173 per cent and 64 per cent respectively over last year. Aircraft orders with both Airbus and Boeing have increased, and deliveries net of cancellation have also risen strong. Airbus has delivered 220 aircrafts YTD this year, relative to 160 last year. Boeing delivered 111 aircrafts YTD, much lower than Airbus, due to production and regulatory issues. This indicates that supply-side in the air cargo industry is likely to respond much better to pricing pressures than ocean cargo.

Cost hike, delays and trade prospects

Industry analysts estimate that shipping delays and pricing pressures will continue until later this year. CIMC reported that its sales of dry containers grew by 174.04 per cent y/y in Q1 2021. This could provide some relief going forward, however, it is not clear how much the production of containers has increased. Maritime trade, which is 80 per cent of global trade, largely depends on container equipment, shipping fleet and the capacity of ports to load and unload goods on the vessels. Renewed surges in infections will further increase already high port turnaround times and will hamper global trade volumes. Increased blank sailings will again aggravate the mismatch of container availability and demand at different ports. The current crisis started as a confluence of demand and supply issues, but now has solely become a story of supply-side bottlenecks. Consequently, it is expected that trade flows will see further delay in shipments and potential rise in prices of electronic appliances and other consumer goods, which have seen higher demand recently. This will become more prominent as demand gets further fuel in large consumer markets like India.

Global growth projected by IMF at 6 per cent in the April 2021 Economic Outlook will be likely revised downward as merchandise trade faces greater uncertainty. IMF projected merchandise trade volumes to grow by 9.5 per cent in 2021, which was largely based on the movement in volumes for first two months of this year. The stimulus payments in US helped spike the demand in March, and most likely demand will shoot up again as the next round of stimulus comes around. But there may not be enough capacity to supply that rising demand, causing the largest quarters, in terms of trade volumes, to see another year of tepid activity. Recovery to pre-pandemic levels may be possible but recovery to those trends will surely come more gradually.

Comments