China recently announced its own sustainable cotton certification system retaliating BCI's decision to revoke ties with Chinese producers. Eventually, this system may not be a truly separate one from BCI and other equivalent standards given China's dense integration in the global market and BCI's large presence in sustainable cotton market. A report.

At present, important developments are taking place in the global cotton marketplace. The reports of forced labour in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region in China led to a boycott of Xinjiang cotton by global brands and consequently a boycott of many of these brands by the Chinese people. Better Cotton Initiative, which is a renowned industry standard to certify sustainable cotton across the world, announced revocation of any business dealings with cotton producers in China.

There have been two important recent developments related to Xinjiang cotton. Firstly, there is anecdotal evidence that while export orders for Chinese yarn and fabric companies took a sharp hit early this year, sales and orders of domestic apparel and footwear brands in China saw a surge as a reaction against foreign brands boycotting Xinjiang cotton. Secondly, China recently made a formal announcement for its own sustainable cotton certification system, Cotton China Sustainable Development Programme, parallel to the internationally renowned Better Cotton Initiative (BCI) and other equivalent standards.

Sustainable cotton certification standards define features of what sustainable cotton is and provide linkages to source such cotton for the buyers. BCI stipulates certain features of sustainable cotton such as maintaining soil, water quality and less harmful impact on the environment, and includes promoting decent work and effective management system as important characteristics. At present, BCI is the largest sustainable cotton system internationally, and sustainable cotton certified by BCI and other equivalent standards globally, have already reached 22 per cent of global cotton production in the 2018-19 cotton season.

It is important to clarify that China is not the first country to have a certification system other than BCI. Many other countries have their own certification standards. Most notably Australia's myBMP standards, Brazil's ABR standards and Cotton Made in Africa standards were adopted by multiple African countries. However, the three latter systems are now recognised to be equivalent standards to BCI, which gives sustainable cotton from these regions greater leverage. In this note, we will explore if China's certification system will be completely independent (as the industry bodies in China label it currently) or will it end up as a BCI equivalent system.

Can China and the world do without each other?

Xinjiang produces more than 85 per cent of China's cotton, and China imports at least 15-20 per cent of its cotton consumption needs every year. As much as Chinese textile producers would want to maintain their relevance abroad, the current environment of speculations against Xinjiang cotton and resulting reactions doesn't help them. China's textile related exports are almost 15 per cent of its overall exports, apparel being the largest category. While international market is attractive for Chinese textile producers, is China's domestic market enough to replace foreign demand if it comes to that?

China's consumption demand had been rising strong since the Global Financial Crisis, much higher than its GDP growth rate. Final Consumption Expenditure to GDP ratio has risen from 48.9 per cent in 2010 to 56.0 per cent in 2019. The pandemic may have hampered its growth in 2020, but recent numbers suggest that retail sales grew by 34.2 per cent y/y in the March-21 quarter. China's growth performance is even more stark in the textile industry, where it still holds huge relevance to global demand.

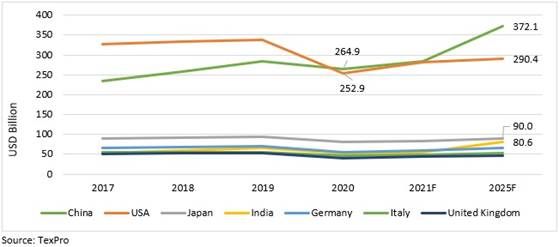

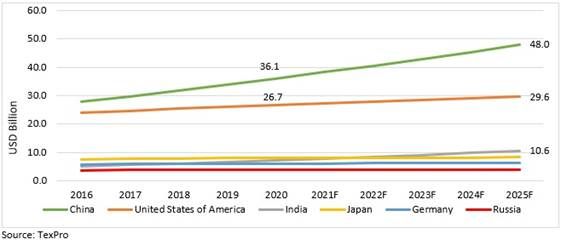

Market size data from TexPro shows that China had already surpassed the US in 2020 for retail apparel market and is expected to grow much faster in the coming years. China's apparel market is expected to reach USD 372.1 billion by 2025, growing at a CAGR of 7 per cent between 2020 and 2025. China's home textile market might also grow much faster than in other countries. From the current value of USD 36.1 billion; it is expected to reach USD 48.0 billion by 2025, growing at CAGR of 5.9 per cent. India remains the only large economy with a higher CAGR than China in both the markets, however the size is much smaller. India's home textile sector is expected to be valued at USD 10.6 billion, less than one-fourth the size of China's market. In apparels also, India's market will be less than a quarter of China's market. In both the markets, India and US cumulatively will also fall short of China's size.

Figure 1: Apparel market size of different countries

Figure 2: Home textiles market size of different countries

These figures are relevant to put in perspective in how the world looks at China today. If global brands continue to boycott the largest market for apparel, the alternatives will have to make greater economic sense as well. It is still early to say something with certainty, but as far as market size is concerned, ignoring China could not be a long-term strategy for global brands. In the current political logjam, losing business worth the size of China could be crucial for sustenance of many of them. H&M has the highest number of stores in China and Hong Kong, and the region overall constituted 5.7 per cent of H&M's total net sales in 2020. China and Hong Kong combined were the fourth largest market for H&M after Germany, US and UK. Nike Inc which was the second largest apparel company by sales in 2020 (Forbes 2000 Global Companies), gets almost 15.9 per cent sales from Greater China. China exports almost 33.0 per cent of apparel & clothing accessories globally and attempts by global brands to shed all ties with it are expected to be nothing but purely gimmicky.

Amidst the recent hullabaloo over boycotting Xinjiang cotton, China's move to announce a parallel certification system for its sustainable cotton is noteworthy. As much as one would like to believe that China could rely solely on its domestic brands and market for consuming the largest stocks of cotton in the world, this should not be an obvious conclusion. Currently, China consumes almost all its domestic cotton, of which Xinjiang supplies almost 85.0 per cent. China is also the largest producer and consumer of cotton yarn, consuming almost USD 38.9 billion in 2019 (Source: IndexBox), and exporting only USD 1.1 billion. China's exports of cotton woven fabric were USD 12.9 billion in 2019, more than six times that of the next largest exporters of cotton fabric--Pakistan and India. Global brands cancelling orders in China against Xinjiang cotton is not sustainable also because Bangladesh and Vietnam are the largest consumers of cotton fabrics coming from China and shunning these two markets along with China is the last thing apparel companies would want to do.

China's dependence on global brands is largely based on the humongous volume of exports of apparel it sends to the world. The international brands also have strong presence in China and serve much of retail apparel needs. However, if things go as they stand, this might change. Large brands such as Adidas & Nike have the largest market shares (as per Statista, 2.2 per cent and 2.1 per cent respectively) in apparel & footwear in China, but local brands such as HLA, Anta and Li-Ning are not far behind. Recently the sales of these local brands boomed as sales of Nike and Adidas took a beating.

As much as large international brands can't give up the largest fashion market globally, China also won't be able to avoid exporting to the world, which is largely under the banner of these very brands. China exported around USD 145 billion worth of apparel to the world in 2019, while its domestic market was USD 264.9 billion. No doubt, China's market is larger in value than many markets put together, still the global market holds much more relevance. It is hard to accept that global trade is a two-way street. China has established itself as such as an important cog of this global machinery, that it won't be without severe consequences if it comes to complete stifling of relationship between rest of the world and China.

Relevance of the separate sustainable cotton certification system

Harking back to the announcement about a separate sustainable cotton certification system in China--the details of this, which would include the features defining sustainable cotton, aren't clear yet. But it isn't hard to conclude that it can't be a completely independent system from BCI. One big factor is that it is hard to trace cotton fibres at the stage of fabric or after. Vietnam and Bangladesh depend heavily on fabric imports from China. They could possibly import fabric from Pakistan, India or Turkey, but the scale and quality differences make replacing China entirely, less likely.

Another important aspect is if China's sustainable cotton certification develops parallel to BCI, and Chinese brands and consumers embrace it. Some possible impacts of this could be-China's sustainable cotton (as notified by its own certification system) will perhaps not be recognised as sustainable cotton globally. Chinese fabric exports will shrink dramatically as international brands will move to other sources of cotton and particularly sustainable cotton, noteworthy ones being Brazil, Pakistan, India and African countries. Chinese brands will also be largely restricted to the domestic market as in such a scenario, global acceptance of these brands will become doubtful. Sustainable cotton is projected to grow to 30 per cent of global cotton production, and Better Cotton and equivalent standards constitute almost all of it. From the perspective of promoting sustainability, having uniform standards are generally considered more helpful. Separate certification for a large producer like China would perhaps only suffice its own needs but might not be embraced by rest of the world alike.

As elaborated above, it is not in anyone's interest to shrink global trade with China. Both the world and China tend to lose from it. As much as building a separate certification system signals retaliation to western hegemony right now, the consequences from this are only for one to imagine. Global brands will find it hard to remain out of China, and so would China and its brands not to be able to trade with the world. In such a scenario, making China's Sustainable Development Programme truly independent of the already established global standards appears to be a mere play of words and is expected to perhaps become an equivalent standard to BCI in the time to come. This is, of course, assuming both China and global brands want no further hurdles to trade and economic growth.

Comments