India’s new foreign trade policy (FTP) is under formulation and will take the baton of boosting India’s exports after a decade of weak performance. Current FTP consolidated previous export promotion schemes and attempted to ease compliance, but results were below expectations. In this note, we discuss India’s export performance and scope for further change.

India’s new foreign trade policy is in formulation stage and will be announced and implemented soon to give direction to our trade for the next four years. It is undoubted that higher trade growth leads to higher economic performance. As an economy becomes more trade oriented, its resources are more efficiently allocated to sectors which add greater economic value, ideally producing goods which it can produce relatively at a lower cost, resting other products to be produced elsewhere. All major industrial nations we know today have all focused heavily on trade (not just exports) along their high growth phase, to remain competitive and increase growth.

It is easy to note that higher exports growth pulls Gross domestic product (GDP) growth up, and lower exports growth pulls it down. Also, on the rising side, exports generally grow faster than GDP. One obvious way to look at it is since export is just one component of GDP, GDP growth will be an average of growth in exports and other components. But more dynamically, the impact on GDP growth is much more than just the growth in exports. Economists have documented that resource efficiency is larger in export-oriented sectors than non-export ones, and as export sectors grow faster, the competition for these resources leads to a spill-over of this efficiency to other sectors in the economy as well. This perhaps explains why GDP growth lags exports growth as this externality to other sectors takes time to set in and resource allocation adjusts to a more optimal one. Also, technological flow to export sectors is much faster as global competition leads to search for more cost reducing methods of production.

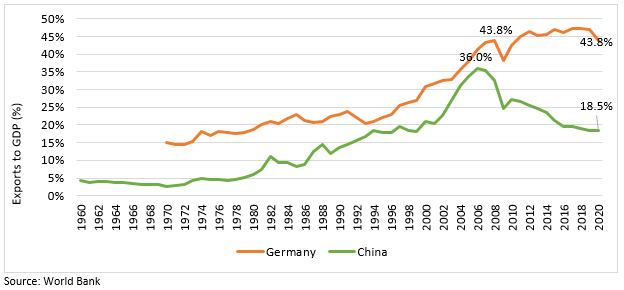

This fact is evident in perhaps all countries with very high export growth but case in point is two of the most industrial nations today–Germany and China. Post the 1990s, as the Berlin wall fell and economic integration of West and East Germany took place, more global integration of Germany pushed its growth higher. Exports to GDP kept moving higher (still hasn’t plummeted) as exports grew much faster than GDP. For China as well, beginning in 1990, its high growth phase had extremely high export growth as the main contributing factor till 2008. Post that, China has relied more on domestic consumption for growth, and its average growth has fallen tremendously from 17.7 per cent in 2001-10 to 10.1 per cent in 2011-19.

Figure 1: Exports to GDP of Germany and China

India’s trade performance moderated post Global Financial Crisis (GFC)

India’s overall economic performance in the last decade was far from impressive. An average nominal economic growth of 6.3 per cent between 2011-19, fared poorly with its remarkable run in the decade 2001-10, when its nominal GDP grew at an average of 13.9 per cent. The last decade was also one of consumption led growth, as the export performance failed to impress. On this front, it is now an almost accepted notion that sluggish global demand kept India’s exports from growing. While global demand had a significant role to play, India’s export performance had more to do with its own policies. Global economic recovery did face an unexpected slack in the last decade post the GFC, however newly emerging exporting countries such as Bangladesh and Vietnam still outperformed rest of the world with their export performance.

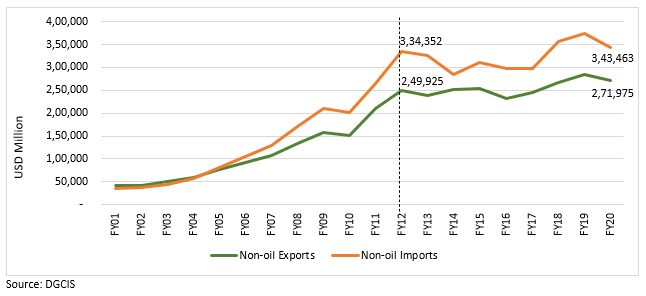

India’s non-oil exports grew from $42.7 billion in 2001 to $150.6 billion in 2010 at a CAGR of 15 per cent, while its growth in the next decade (2011-19), plummeted by almost 50 per cent, registering 7.3 per cent CAGR. An important question to ask is whether export is only a function of external demand. Figure 1 points us to an important and widely known aspect of international trade that lower imports restrict a country’s exports as well. As India’s non-oil exports have remained almost stagnant from 2012 onwards, its non-oil imports have also grown slightly. To the extent that much of these imports lead to production for exports, barriers to import flows hurt exports as well as economic performance. Policies of import substitution that sound almost perfect from a political standpoint, have time and again been shown to be detrimental to the economic growth.

Figure 2: India’s non-oil exports and non-oil import

Dr Arvind Panagariya (professor at Columbia University) in his article last year elaborated how India had historically experimented with import substitution and its failures and the need for policymakers to recognise its perils. India recently has adopted a slightly aggressive approach to import substitution with its border tussle with China becoming of greater concern. Higher import duties on electronic goods imposed in 2017 has led to only a slight reduction in imports, while exports have yet to show any signs of pick-up. Touted to bring cost advantages to India’s electronic goods manufacturing industry, the attempt at import substitution ignored more deeper causes of India’s manufacturing disadvantages. Exim Banks’ recent note on boosting India’s manufacturing through import substitution scarily implies this strategy as suitable for many other sectors to achieve growth and scale. For some industries such as pharmaceuticals and solar cells, this strategy perhaps becomes crucial as Indian industry could prove its potential if it is not competing with state enabled lower prices by Chinese companies. For other industries, where Indian industry has proven its prowess, for instance, steel, such a policy will perhaps be not required. Very rightly, the note mentions that Indian industry needs to invest more in state-of-the-art technology and reduce maintenance costs to gain competitive advantage.

Dr Arvind Panagariya (professor at Columbia University) in his article last year elaborated how India had historically experimented with import substitution and its failures and the need for policymakers to recognise its perils. India recently has adopted a slightly aggressive approach to import substitution with its border tussle with China becoming of greater concern. Higher import duties on electronic goods imposed in 2017 has led to only a slight reduction in imports, while exports have yet to show any signs of pick-up. Touted to bring cost advantages to India’s electronic goods manufacturing industry, the attempt at import substitution ignored more deeper causes of India’s manufacturing disadvantages. Exim Banks’ recent note on boosting India’s manufacturing through import substitution scarily implies this strategy as suitable for many other sectors to achieve growth and scale. For some industries such as pharmaceuticals and solar cells, this strategy perhaps becomes crucial as Indian industry could prove its potential if it is not competing with state enabled lower prices by Chinese companies. For other industries, where Indian industry has proven its prowess, for instance, steel, such a policy will perhaps be not required. Very rightly, the note mentions that Indian industry needs to invest more in state-of-the-art technology and reduce maintenance costs to gain competitive advantage.

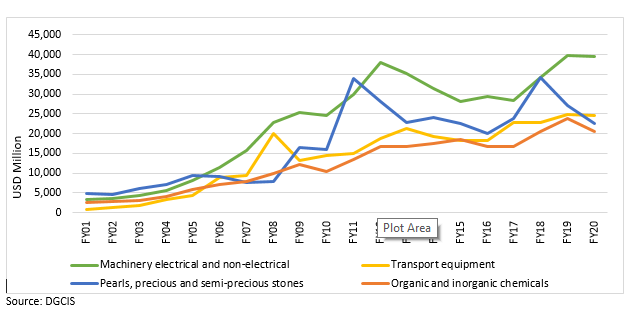

The last decade in India has also seen dwindling imports of key industrial goods, implicitly or explicitly, as there is import substitution in many industries. Imports of machinery and transport equipment have seen sluggish growth over the last 6-8 years, impeding export performance of our industries to an extent. Similarly imports of key intermediates used in India’s export sectors have also remained almost stagnant over the last decade hurting performance of key export sectors which use them heavily. Only more recently some of these policies have been reversed. For instance, government recently cut import duty on pearls and precious stones which is expected to provide immense relief to India’s gems & jewellery exports.

Figure 3: India’s imports of key industrial inputs

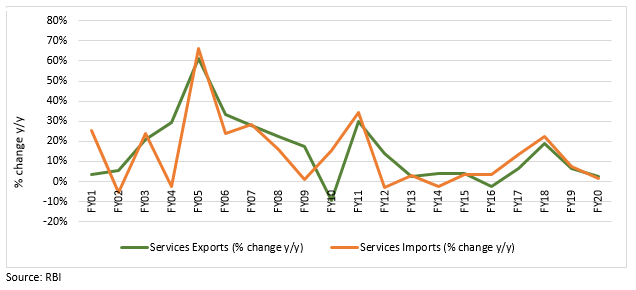

Also, services trade has seen a sharp deceleration post GFC. Services remain a stronghold of the Indian economy as it has relative cost advantages. India’s trade performance on the services front has perhaps more to do with global demand as world services exports growth also plummeted sharply over the last decade.

Figure 4: India’s services trade growth

Current foreign trade policy could achieve very little

The current foreign trade policy (FTP 2015-20) introduced various measures focused on boosting India’s export performance. On the merchandise side, the focus remained on Make in India in order to manufacture some of the highly imported goods within India. To boost India’s exports, the government put in place two schemes: 1) Merchandise Exports from India (MEIS) scheme and 2) Services Exports from India scheme. Both these schemes were brought into place to improve ease of doing business, simplify procedures, promote paperless processing of claims and increase trade facilitation. MEIS in its essence was perhaps only a consolidation of the previous schemes.

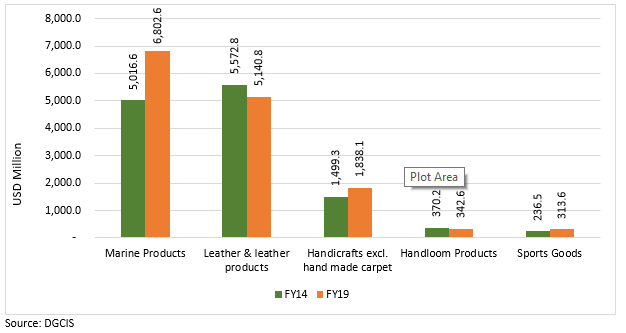

The stated objective of the foreign trade policy 2015-20 was to increase employment and value addition domestically by making Indian products globally more competitive. In those terms, however, the policy can be said to have a limited impact. Exports grew at a meagre 7.9 per cent nominally (2.4 per cent in real terms) between FY15 and FY20, while imports showed a nominal growth of 5.7 per cent (4.4 per cent in real terms). Exports fell short by almost ₹20 lakh crore or 36 per cent of the targeted ₹58 lakh crore by FY20. Some of the sectors such as handicrafts & handloom products, marine products, sports goods etc were to be given special focus through separate exemptions. Export performance of these sectors except marine products during the policy period also couldn’t reach up to expectations.

Figure 5: India’s exports of select principal commodities

One of the more recognised and celebrated achievements of FTP 2015-20 was improving India’s ease of doing business ranking and reducing logistics cost in India. India’s ease of doing business ranking improved from 142 in 2014 to 63 in 2019, on the back of regulatory reforms related to construction permits and ease of getting electricity connection. However, India still fares poorly on other key metrics such as starting a business, registering a property, and enforcing contracts ranking 136, 154 and 163 respectively in 2020.

The greater part of the export promotion schemes (EOUS/SEZ/EPCGS/EHTPS/BTPS/DIES/MEIS) that India has adopted were challenged by the US recently in WTO citing violation of certain provisions of World Trade Organization (WTO’s) subsidies and countervailing measures. The contention was that these schemes are explicit export subsidies (incentives based on export performance). This led to implementation of the Remission of Duties and Taxes on Export Products (RoDTeP) scheme early this year which provides for remission for all taxes and duties levied on export products.

What could be taken up under the new FTP?

What it means for India’s trade measures going forward is that India will not be able to rely on formerly used export promotion measures and will have to come up with more institutional ways to improve its export performance. The newly formulated RoDTeP scheme will be formalised as revised rates are still being deliberated. The earlier trade policy couldn’t achieve much on reducing structural issuesthat hampered India’s exports such as certifications, cost of credit, FTAs etc, and it is expected that more focus will be on these.

It is clear from our past experiences that monetary incentives to provide income or cost support to our exporters have not had substantial dent on our export competitiveness. It is widely documented that India’s products are of lower quality (in general) and quite often fail to match global quality standards. Additionally, less reliance on accreditation by internationally accepted bodies such as National Accreditation Board for Certification Bodies (NABCB) for quality certification poses a much greater challenge for acceptance of Indian goods abroad. It then becomes imperative that the new foreign trade policy addresses this concern and sets up a framework to build comprehensive set of standards that align with global benchmarks, streamline certification of products through proper accreditation channels and establish financial support for firms to match up to those standards.

Lack of appropriate working capital credit also remains a concern for exporters and has been one of the key reasons for slow growth of India’s exports. Large collateral requirements, high compliance costs keep marginal exporters from accessing required credit for their businesses. The government has increased the corpus of Export Credit Guarantee Corporation of India (ECGC) recently but access to credit remains a critical issue.

India’s performance on its Free trade Agreement (FTAs) has also been recorded as less than optimal. Although, the economic survey FY20 reported moderate overall gains for both manufacturing and overall merchandise exports from all foreign trade agreements, there is scope for reaping more benefits. Key reasons identified for lower benefits out of FTAs for India are – low awareness about these schemes, poor participation of industry in trade negotiations, high cost of FTA compliance etc. On these fronts, the government has already taken measures like implementing a system for availing digital certificate of origin, and possibly more reforms could be put in place to increase awareness about provisions under relevant trade agreements.

Recently, Indian Government launched the “Atman Narhari Bharat” initiative which primarily focuses on boosting India’s manufacturing industry and export performance. As part of this initiative, the government initiated the Production Linked Incentive (PLI) scheme identifying 12 critical sectors where both domestic and foreign investment will be attracted to bring economies of scale. But there are misnomers about what would “Atman Narhari Bharat” translate to into actual policy. As the government officially maintains, it does not mean to be inward looking and self-sufficient. It will be of tremendous value to now translate this in very clear terms under the new foreign trade policy with as little restrictions to key imports as possible.

Comments