Madagascar emerged as a textile centre in Africa after many Mauritian and Chinese firms relocated their operations there in early 2000s. However recently, Madagascar has lost its sheen due to continued political instability. Now both socio-economic crisis and technological advancements in apparel production pose challenges to its textile success.

The textile sector in the previous two decades became an absolute example of the flying geese model of industrial and economic development as firms diversified out of China to neighbouring Asian countries and some of the smaller African economies. Countries such as Mauritius, Madagascar and Ethiopia caught on as the African textile hubs, largely because of extremely favourable market access to the US and EU, relatively cheap labour and better economic and political outlook. Amongst the many newly industrialised African countries, Madagascar is a special case for this note for two reasons: 1) being part of the African subcontinent, it holds potential for greater participation in global textile supply chains and 2) with political risk increasing and investments flowing out recently, it might lose steam sooner than expected. There is a technological aspect to the economic development story of Madagascar which we will cover as well. With this analysis we want to explore which one of the paths has a greater likelihood and what possibly lies ahead for Madagascar in its textile ambitions.

Madagascar’s impressive economic run and textile performance

Madagascar’s GDP increased from $4.6 billion in 2000 to $13.7 billion in 2020, while its per capita income rose from $293 to $495 during the same period. As has been the case with other emerging markets, this was facilitated mostly by increased industrialisation and exports. Key factors that led to this upward movement were easy market access through preferential trade pacts such US’s African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) and EU’s Everything But Arms (EBA) & Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA), and Madagascar’s relative success with Export Processing Zones (EPZs). US and EU still dominate Madagascar’s total apparel exports; however, other partners have gained share. Clothing factories in Madagascar are known to produce garments for several global brands such as Zara and JC Penney among others. Foremost of reasons for choosing Madagascar as a sourcing location are its relatively cheaper and easily trainable manpower, easy regulations, good quality products and easy access to markets in US and EU. Not very surprisingly, Mauritian firms set up their first subsidiary units in Madagascar back in 1990s, shifting more labour-intensive manufacturing there. This trend is similar to the relocation of industries from China to neighboring Vietnam in search of more competitive costs.

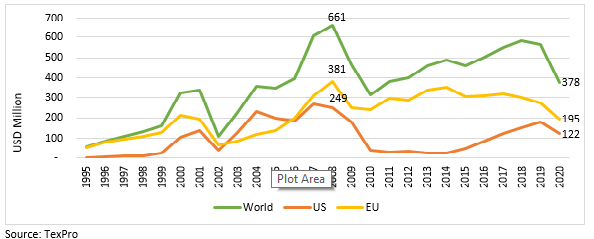

Madagascar’s exports of textile & apparel (T&A) are largely made of apparel, with a dominant share of woven clothing. Its T&A exports are the largest category in its total exports and the sector employed almost 400,000 people as of end of 2019. Its exports to the US picked up sharply in early 2000s, growing faster than exports to EU, as African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) came into place, while EUs Everything but Arms (EBA) and Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA) came later. However, with political instability rising around 2009, Madagascar was removed from AGOA and was only recently included back. This impacted its apparel exports to the US, while its exports to the EU continued to grow. However, its trade with EU has faltered recently as exports to US picked up again.

Figure 1: Madagascar’s apparel exports to World, US and EU

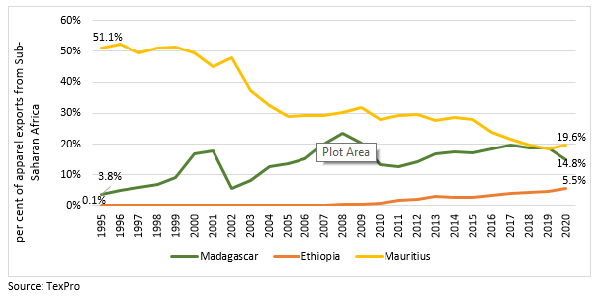

Not just in absolute terms, Madagascar has had a stellar run over the past two decades even relative to other African nations. Figure 2 shows how rapidly Mauritius lost share in apparel exports to Madagascar predominantly and other neighbours like Ethiopia. Several of the Mauritian textile firms also shifted more labour-intensive parts of the supply chain to Madagascar as rising cost of production and political instability made them less feasible domestically. This trend has however diminished over the years. Mauritius’ FDI flows into Madagascar relative to total Africa has come down from more than 20.0 per cent in early 2000s to now an average of 8.9 per cent since 2015.

Figure 2: Share in apparel exports from Sub-Saharan Africa

Madagascar’s comparative advantages and disadvantages

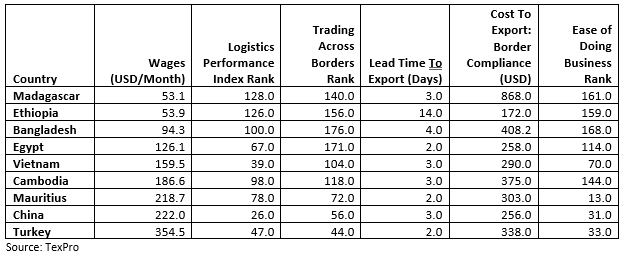

More recently, with greater preference for diversification in textile sourcing by major global brands, there has been general optimism about development of textile industry in the African subcontinent and the region becoming the next supply hub for many years. On a labour-cost perspective, the African textile hubs perhaps fare much better than their Asian counterparts, but it is important that we look at other economic factors to gauge real competitive advantage that Madagascar offers. Table 1 shows that Madagascar has tremendous advantage in terms of labour costs, with the lowest wages amongst many emerging textile supply markets. It also compares well in terms of lead time to export indicating that its ports are extremely competitive and exports delivery from Madagascar are timely.

Madagascar has its shortcomings as well. On the overall Logistics Performance Index, it ranks 128th, much lower than its counterparts. While its lead time to exports is impressive, the cost of border compliance ($868.0) is more than double that of Bangladesh ($408.2) and almost three times that of Vietnam ($290.0). Its ease of doing business ranking is 161.0, lagging tremendously in access to electricity and credit, construction permits and enforcing contracts.

Table 1: Relative comparison of select textile producing countries

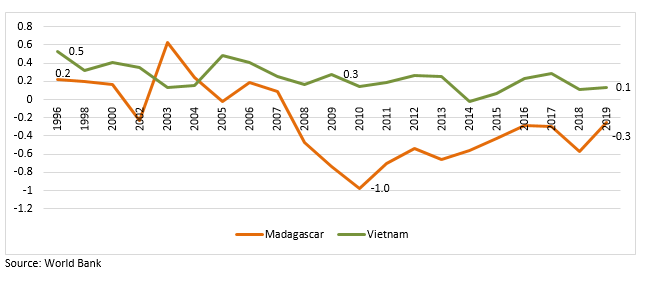

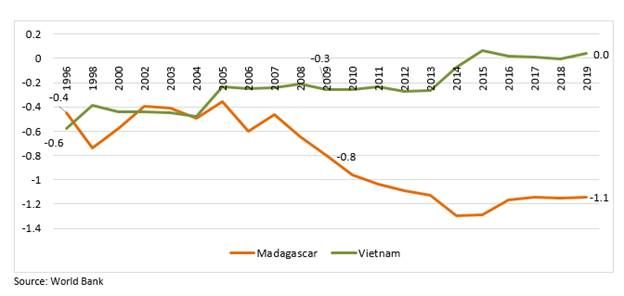

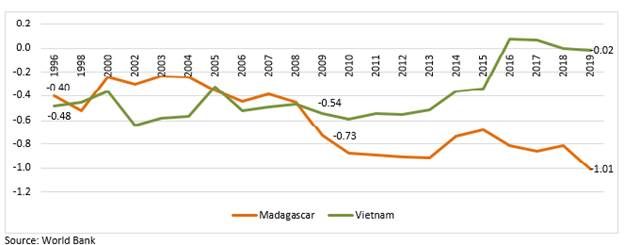

The reason which led to Madagascar’s exclusion from the AGOA in 2009 was an unelected military government following a coup on the earlier democratic government. The country managed to go back to electoral politics by 2013, however, the political scenario remained highly unstable. In the years post 2009, the political and (somewhat) the economic environment in the country continued to deteriorate. Figure 3, 4 & 5 reflect Madagascar’s performance on three governance indicators published by the World Bank. For comparison, let us also look at Vietnam which has consistently improved on these metrics.

Figure 3: Political Stability and Absence of Violence/Terrorism (World Governance Index)

Figure  4: Effective Governance (World Governance Index)

4: Effective Governance (World Governance Index)

Figure 5: Rule of Law (World Governance Index)

While post the regime change in 2013, political stability has significantly improved, it has yet to gain as much credibility as before 2009. the return of democratic governments has not had much impact on the overall political environment. Madagascar’s performance on governance and maintaining rule of law has continued to deteriorate further. With the ongoing situation is still very dire, it may take longer for Madagascar to pose itself again as a safe place for the industry. As reflected in an article for Institute for Security Studies , the political turmoil continues unabated (with another coup attempt) and severe socio-economic crisis boiling for the island nation.

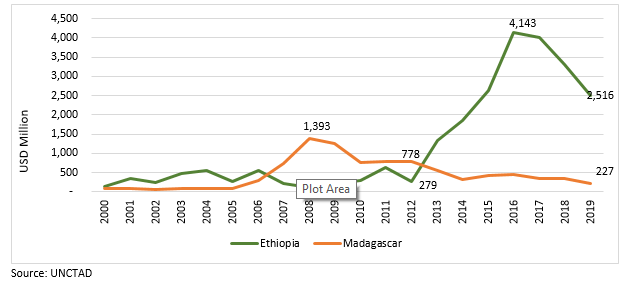

The political turmoil has led to tremendous damage to the country’s image in the minds of foreign investors. FDI inflows to Madagascar have come down rapidly over the years while flows in neighbouring Ethiopia have increased sharply. Since much of the apparel production in Madagascar was facilitated by investments by arms of foreign companies, slowing investment flows implies lost apparel production, exports and economic growth.

Figure 6: FDI Inflow

Riding against the technological tide

While the political situation in Madagascar remains murky and has impacted its prospects of raking tremendous share in textile supply chains, there is yet another factor which determines its chances of success. The interplay of technology in the apparel production process has yet to materialise at a commercially viable scale, but experiments on automating the last mile of apparel production (cut & sew) are underway. Companies such as SoftWear already has automated sewing robots on the market called “sewbots”, which can potentially reduce the amount of labour required and improve productivity.

Why this holds relevance for countries such as Madagascar? Because even though this technology has yet to be commercially adopted, when it does get adopted, it could drastically reduce global brands’ search for cheap labour countries for sourcing garments. The search for next best alternative to rising domestic labour costs will probably become less important, when increased productivity through automation is able to justify its costs.

In our earlier article, we had covered how China’s changed course on economic development will contribute to the technological movement in textile value chain. Much of Africa’s investment comes from China, which holds true for Africa’s textiles production as well. Altenberg Et Al’s paper covering prospects of Ethiopia and Madagascar records relocation prospects of some of the largest Chinese textile players. The paper highlights that while Chinese textile firms still seek relocation as an alternative for optimising on rising labour costs in China – a) African countries are not necessarily the most preferred choice and b) use of labour-saving technology in factory tasks has increased tremendously, if not in actual production of garments. The fact that being closer to their established networks in China makes more economic sense, relocation to African countries by Chinese textile firms has remained a very small proportion of their overall investments abroad.

Madagascar has historically gained much from influx of labour-intensive textile manufacturing facilities and it may still have time against the technological tide to reap as much benefit. The recent announcement of a Special Economic Zone (Moramanga Textile City) dedicated to textiles in collaboration with Mauritius-Africa Fund promises great dividends for Madagascar’s textile ambitions. The textile hub would require an investment of close to $200 million and can potentially generate close to 200,000 jobs both directly and indirectly.

This move is timely as the region has some time to attract textile manufacturing investment on the back of lower manufacturing costs and technological clock is ticking slow. Although, by what Altenberg Et Al conclude in the paper, Ethiopia holds greater promise than Madagascar, which is reflective in the FDI trends recently both from China and other African nations like Mauritius. Madagascar’s only shot at revitalising interest in its textile capacity is if the Moramanga Textile City becomes a success. Even then much depends on how the island nation brings back political stability sooner. The risks involved with the latter are much greater to compensate by just lower labour costs.

Comments