A lot is going on in the supply chains currently, with the logistics industry facing unprecedented challenges. Shortages around the industry are pushing prices higher both directly and through higher energy and fuel costs. These are perhaps short-term factors which some economists expect to ease by early or mid next year. However, for the longer term, the most crucial aspects for supply chain revolve around geo-politics.

The geo-political relations are a significant factor in determining the direction of supply chains in the near future, and much is happening on that front slowly but surely. Apart from China’s own measures to assert dominance on many counts, countries are now speedily forming alliances to counter China’s might both economically and strategically.

Recently, a meeting was held to strengthen the QUAD network, where the four countries (Australia, India, Japan & US) agreed to collaborate on high-standards infrastructure, combatting the climate crisis, emerging technologies, space & cybersecurity. Also, the AUKUS (Australia-UK-US) submarine collaboration to counter China’s presence in the South China Sea implies tremendous pressures in other arenas of economy. Below is an overview of how textile and apparel supply chains look like right now, in terms of investments and trade, and what kind of future movement are then to be inferred from these trends.

China has remained in the headlines recently as its domestic economy faced headwinds on several fronts. Earlier this year, it faced global pushback on Xinjiang cotton and many international brands were vocal about forced labour issues there, which authorities in China have completely denied. Later, a renewed surge in COVID-19 infections stalled port operations making transporting goods out of China extremely tough, which is now an even bigger challenge as more containers pile up at the ports1 . This has impacted China’s economy tremendously in the recent months, reflected in China’s Manufacturing PMI for Sep ’21 (49.6)2 and Oct ’21 (50.6), indicating very sluggish growth or a possible contraction in China’s manufacturing sector in the coming months. More recently, power cuts due to coal shortages and the scare of China’s huge real estate debt made its economic prospects look even worse, as covered in our previous note.

As much as these concerns and the resultant impact reflect China’s dominant participation in global economy, from a long-term perspective also, China holds a dominant position in global business and investment decision making. Global investment community continues to be positive on China, however their perspective likely reflects more of a wait and watch approach. Some of the big names in global investment industry are still bullish on China, and some are probably more optimistic than before.3 This is also seen in the FDI inflows in China this year, which climbed 23.4 per cent y-o-y to $142 billion in Jan-Oct 2021.

Despite the short-term speculations about US-China trade war affecting their trade relations and global supply chains becoming more diversified shunning China’s supplier networks, China’s contribution and relevance to global trade and economy will perhaps continue to grow. And it’s not just what EU and the US commit in policy terms with respect to China, but also China’s own foreign partnerships in terms of trade and investments across the world that are now widely known.

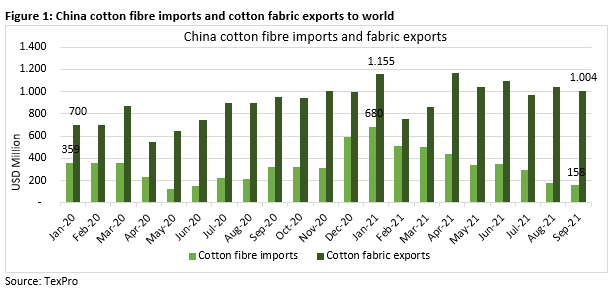

In the immediate short-term, while many expected China to increase the use of imported cotton as sentiments towards Xinjiang grew coarser, demand of Xinjiang cotton has kept its pace. China’s cotton imports, which would otherwise compete with domestic cotton supplies, have slipped lately reflecting that domestic demand for China’s home-grown cotton has remained unharmed.

Exports of cotton fabric from China have also remained strong recently, reflecting its dominant position in this segment. The speculation that China’s cotton and textiles made out of it continue to be in use has been recorded elsewhere as well4 as experts recognise China’s bumper cotton harvest amidst concerns about its forced labour issues. However, strong demand for cotton fabric from China suggests how difficult it could be to actually diversify input sourcing. This was also evident when apparel producers were running short on deadlines as supplies of fabrics from China dried up suddenly last year.

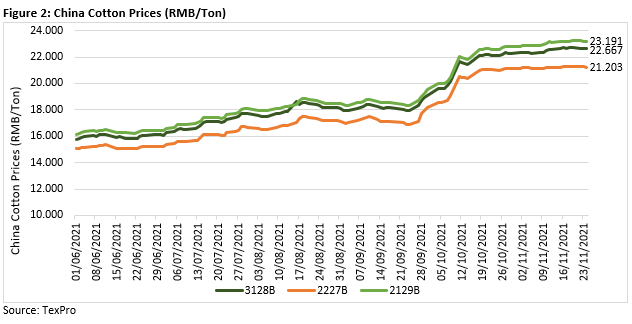

Cotton prices in China’s domestic market have also remained strong. All three major categories in China have had a steady demand in the last couple of months, with prices inching upwards (Figure 2).

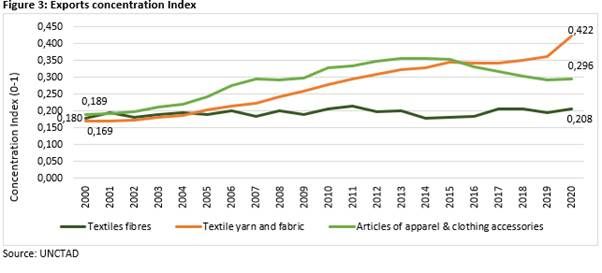

The mid-stream segments of the textile supply chain are harder to diversify or shift easily as they are more mechanised, require higher investments and therefore, have greater dependencies on established networks to supply inputs. This is reflected in the concentration index for exports (UNCTAD) for the three broad textile industry segments (Figure 3). Yarn and fabric remains the most concentrated segment of all, with a rise in concentration in the recent years. Apparel & accessories exports have now become highly diversified from what they were in 2015. Fibre exports remain the least concentrated segment. An important indication of relocation of industries between countries is the investment flows from the already established markets towards upcoming manufacturing locations, such as Vietnam, Bangladesh, India, Ethiopia, Egypt among others. China has been investing heavily in many other countries (as we will see shortly) and the mid-stream parts of the textile and apparel value chain will be harder to diversify out of China. Perhaps then, the narrative around China is further from the reality, and large shifts in textile sourcing patterns (at least in yarns and fabrics) may not be likely or they will be very slow.

However, some noteworthy changes in the supply chain have already started taking place in the last five to six years, and the sentiments were only aggravated recently due to US-China trade tensions, followed by the supply shock as a result of the pandemic. Although Vietnam and Bangladesh are the most talked about locations for sourcing apparel, more competition is coming up as both United States and Europe have been forging trade relations outside of China. China on the other hand has also been investing heavily in other Asian and African economies recently to supply key raw materials and for apparel manufacturing as well. This solves multiple problems for China related to a) labour costs, b) ambitious emissions reduction targets that China hasn’t been able to match yet, and c) policy plan to diversify out of low value-added segments.

However, as the American Chamber of Commerce in Shanghai’s recently released China Business Report 2021 suggests, almost 72.0 per cent of American manufacturing companies in China are not planning to move out of China in the next three years. More importantly, as local competition grows, a large proportion of the surveyed manufacturers are getting even more invested in the Chinese market. Also, the business sentiment around China is reported to have improved over last year’s and are at similar levels as in 2018.5

China’s diversification

We have talked about China’s diversification plans at length in a previous article, but this was merely from a policy angle and meant diversification perhaps in a narrow sense. From a policy perspective, China is largely focusing on higher value-added products, and that means a vertical diversification. But there is also a horizontal diversification taking place, building manufacturing facilities for inputs in other (relatively cheaper) countries. Diversification in both senses would essentially involve a change in trade basket and investment flows in the economy.

China’s investment flows to other countries highlights a very startling fact about the global textile industry – supply chains are and will become more borderless. Even though something is not produced in China, it will be highly likely that a Chinese company is doing it.

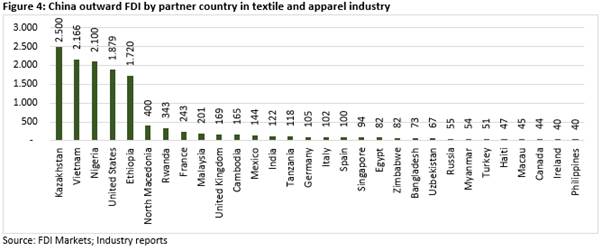

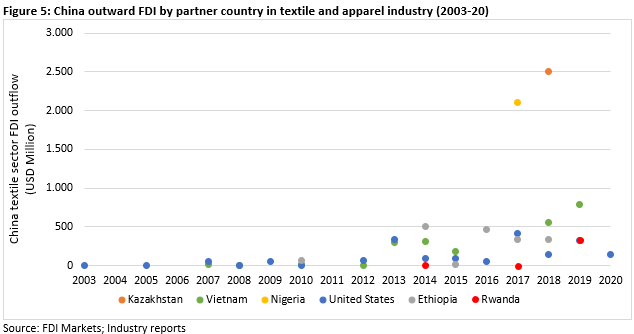

Figure 4 shows the largest investment flows from China from 2003 to 2020 in the textiles and apparel industry. Kazakhstan, Vietnam, Nigeria, United States, and Ethiopia were the top 5 recipients of FDI from China. Also, the top emerging markets recipients such as Kazakhstan, Vietnam, Nigeria, Ethiopia, North Macedonia, and Rwanda cumulatively got 67.3 per cent of the total flows.

Another important feature of these investments flows is that major part of these investments into the mentioned emerging economies has come very recently while its investments in the US have been more distributed over the years, although the flow picked up pace in early last decade (Figure 4). While this data reflects a tiny proportion of the scale of operations in China, its timing might not be coincidental.

Let us look at some of these investment projects and the segments they cater to. It becomes clear that countries such as Vietnam, Nigeria, Ethiopia, North Macedonia, and Rwanda are focused on more by apparel manufacturers while Kazakhstan, United States and EU are focused on for other segments.

To illustrate, the single large investment in Kazakhstan is by Cathay Industrial Biotech, a large manufacturer of bio-based synthetic materials, for producing nylon and other related products. This makes the proposed plant its largest production unit in terms of capacity. In Vietnam, major investing companies included Shenzhou International Group (2019) and Zhejiang Hailide New Material (2018).

Shenzhou’s investment was for garment manufacturing, while Zhejiang Hailide’s investment was for expanding its existing polyester filament plant. The investments in Nigeria are from two Chinese companies – Shandong Ruyi and Huajian Group. The former invested $600 million in 2017 in a textile park in Kano State and is also in the process to invest another $2 billion in a vertically integrated (fibre to garment) facility. The latter invested $1.5 billion putting in place a shoe manufacturing facility. Also, Rwanda received $333 million from Chinese garment manufacturer Pink Mango C&D in 2019.

Remember that these investments are not just pure business decisions but are also strategically important, as they align very well with China’s overall policy and its three aspects mentioned above. Diversifying much of the apparel manufacturing in nearby Vietnam and the African countries makes sense in two ways – 1) relatively lower labour costs bring much larger savings on export revenues as well as on sourcing inputs for their domestic industry and 2) China becomes a strategic trade and investment partner for these countries, strengthening its position in global economy.

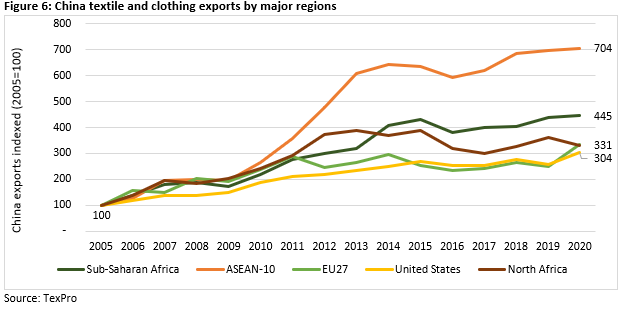

China’s investments in these economies are complemented with increasing bilateral trade flows. China’s trade with ASEAN and African countries has increased with much greater intensity when compared with its investments in these regions. China’s textile and clothing exports to ASEAN and Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) have increased much faster than its exports with the EU, over the last 15 years (Figure 6), and post 2011, China’s exports of textile and clothing to EU and the US have remained relatively flat, while with other two regions has grown robustly.

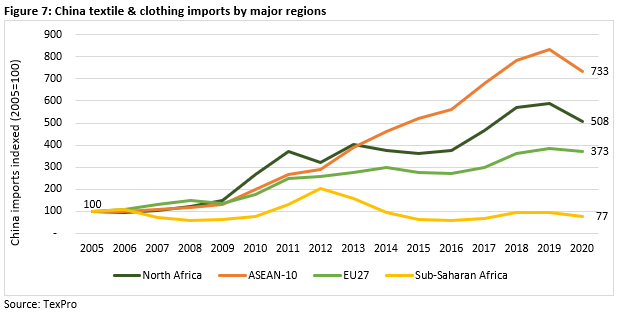

On the imports front, China has started engaging increasingly with the North African countries much more than their Sub-Saharan counterparts. China’s imports from North Africa have increased by slightly more than 5 times since 2005, while its imports from SSA have declined. Again, textile and clothing trade flows between China and ASEAN saw the highest growth over the period.

US and EU diversification

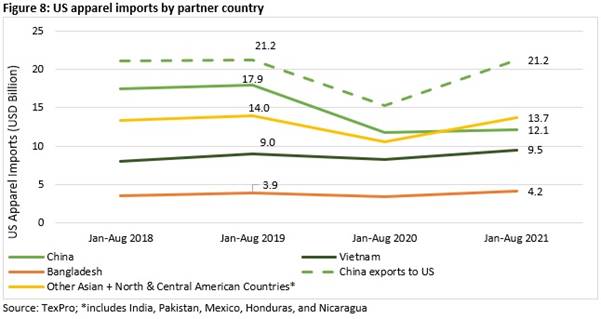

From the perspective of EU and US, China is still an irreplaceable part of the trade in many niche segments. Political tensions heated up in 2020, but trade movement was a lot slower to change. Figure 8 shows US apparel imports from China, Vietnam, and Bangladesh. Looking at this downtrend in 2021 in US apparel imports from China, some commentators have rushed to conclude that US sourcing is majorly shifting away from the latter. However, China’s apparel exports to US data doesn’t suggest the same.

In fact, the divergence between China exports to US have unexpectedly diverged from the US apparel imports from China, due to reporting issue. The issue, however, is not new (data divergence since 2015) and it has only exaggerated. This has also been validated by analysis by the Federal Reserve, confirming that there is both underreporting by US importers and overreporting by Chinese exporters for apparel trade6. Apparel imports from both Vietnam and Bangladesh have jumped up significantly in 2021, gaining a lot of momentum at the expense of China. Apparel imports from other Asian countries such as India and Pakistan, and from neighboring countries like Mexico, Honduras and Nicaragua have also recovered well from last year but are yet to go past pre-pandemic levels.

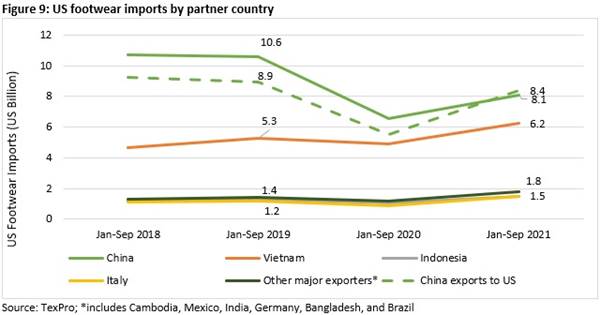

Similarly, in US footwear imports, China’s share appears to be going down which is likely due to the reporting issues mentioned above. However, Vietnam has gained tremendous share lately in US’ footwear market along with European countries like Germany and Italy, and Asian countries like Cambodia, India and Bangladesh.

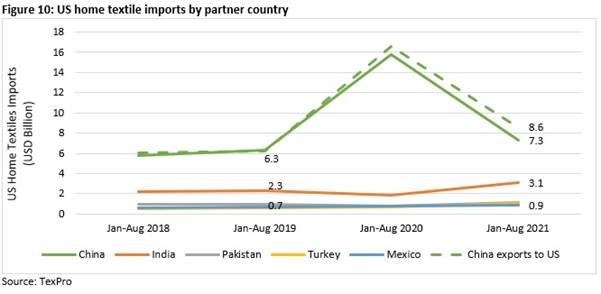

In the home textiles segment as well, the shift from China is not very apparent as the fall in imports from China suggests more of a normalisation in demand. However, Figure 10 shows that imports from India have been the biggest gainer in this segment as India has one of the largest capacities in home textiles globally.

Although these recent trends in US-China bilateral trade reflects a shift, much is left out of the picture. On the policy front, US and China are still at the confrontation stage, and the Biden administration has maintained its position recently to go largely with the measures taken by the previous government and administer China’s compliance on Phase One agreement and revisiting some of the provisions in the agreement itself.

Additionally, as per the recent US-China Trade Strategy, it became clear that bilateral trade relations will see more impact depending on the outcomes of strategic deliberations on issues related to market access, intellectual property, and China’s unfair trade practices7. An important message sent across was that US doesn’t wish to inflame trade relations with China, a positive for global trade and value chains. Although, the formation of QUAD could possibly change the course of interaction between the countries, it is still early to say much.

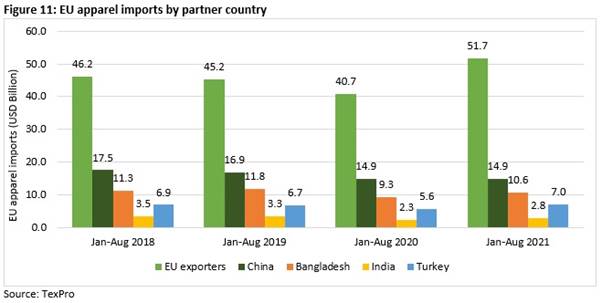

EU’s trade with China has partially matched with the tensions on surface. EU apparel imports from China have now recovered from last year, however they still remain below pre-pandemic levels (down only by 11.8 per cent relative to 2019). Some of the imports may have shifted to Turkey, which have increased tremendously this year, surpassing levels of 2018 and 2019. Other partners such as Vietnam, India and Bangladesh have also seen a remarkable uptick in demand this year, but they are yet to surpass pre-pandemic levels. Sourcing apparel from within the EU has also seen a strong rise this year increasing by more than 14 per cent over 2019.

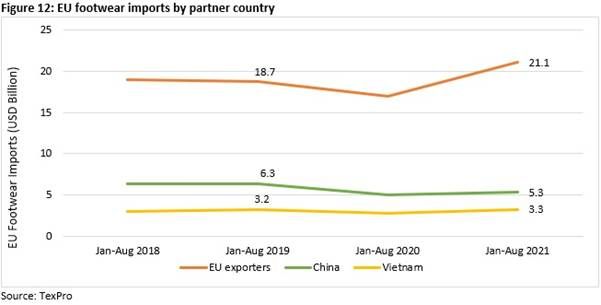

In footwear, EU imports from China have got impacted almost equally as its apparel imports (a decline of 12.8 per cent from levels in 2019). Similarly, sourcing from within the EU has increased sharply. Footwear imports from within EU have risen from $18.7 billion in Jan-Aug 2019 to $21.1 billion in Jan-Aug 2021. This highlights that perhaps EU, as compared to the US, is seeing a much faster switch out of China.

Things in perspective

As many have pointed out earlier, and still do, global trade might not see the growth it enjoyed in the previous decades. It may even see a decline likely from the focus on self-sufficiency that countries have now increasingly come to deliberate on. In addition to that, a move towards a bi-polar or multi-polar global economy could put even greater pressure on existing supply chain directions. These trends as highlighted above, are perhaps the beginning of a larger shift towards diversification, both out of China and on a broader level to reduce tail-risks. Such movements in trade and investment can be expected in the coming years much more prominently.

References:1https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2021/11/major-delays-china-united-states-shipping/

2https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-09-30/china-s-factories-contract-for-first-time-since-pandemic-began

3https://www.bloomberg.com/features/2021-what-investors-say-china-crackdown/?cmpid=BBD093021_CAS&utm_medium=email&utm_source=newsletter&utm_term=210930&utm_campaign=closeasia

4https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/asia_pacific/china-xinjiang-cotton/2021/11/17/fcfe320e-37a3-11ec-9662-399cfa75efee_story.html

5https://www.fibre2fashion.com/news/textile-news/us-firms-foresee-growth-potential-in-china-expanding-there-survey-276546-newsdetails.htm

6https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/notes/feds-notes/did-the-us-bilateral-goods-deficit-with-china-increase-or-decrease-during-the-us-china-trade-conflict-20210621.htm

7https://www.americanactionforum.org/insight/the-biden-administrations-u-s-china-trade-strategy-a-primer/

Comments