The packaging industry accounts for one of the most significant volumes of virgin paper and plastic worldwide. Studies suggest that 50 per cent of paper and 40 per cent of plastic produced per year is used for packaging. However, only 36 per cent of municipal solid waste comes from packaging from all industries.

The fashion sector has been steadily rising over the last decade, and the fashion industry is currently the largest e-commerce market segment. The value of this industry is more than $520 billion per year. It is expected to grow by almost 10 per cent annually to over $1 trillion by 2025 (Holding, 2019).

Not many studies have yet been done that can provide a detailed evaluation of the environmental effects of compostable packaging. Existing research shows that there has been greater emphasis on those in the business-to-business (B2B) packaging industry, demonstrating the need for study on the business-to-consumer (B2C). Reusable packaging is not an immediate solution to all the packaging challenges today (Nelson, 2020).

Retail outlets using cartons or corrugated cardboard boxes frequently find it difficult to finalise the appropriate size for the shipment. These cartons increase the amount of waste to be disposed of. Further, more and more customers are dissatisfied with the amount of packaging that has to be disposed of along with their household waste. Approximately 30 per cent of the CO2 emissions generated due to e-commerce are from packaging used in shipping. Traditional single-use packaging used in shipping is produced, used, and then disposed of. Bigger plastic packaging parts are incinerated or exported to other countries where correct disposal is challenging.

Generally, the protective aspects of the poly bag are the most critical. Protection from dirt, dust, and moisture is an essential aspect. According to a 2018 survey, price sensitivity is also one of the top factors. This implies that most brands do not want to pay more for their packaging. Transparency, or being able to view the garment and its hang-tags, was considered very to somewhat crucial by most companies. However, being able to store garments for an extended period was mostly only considered somewhat to slightly important. Few rated this aspect a top priority compared to the organisational purpose and resistance to tearing and stretching forces. The only option that was not important for most companies was the requirement to meet a logistics or retail partners’ specification – although a handful did describe this as very to somewhat important (Hiatt, 2018).

These days, images of plastic contaminating the marine environment and causing harm to flora and fauna and the ecosphere are in the public focus. Since every garment is shipped in a poly bag, more than 150 billion poly bags could be produced annually. Customers and staff complain about the amount of plastic packaging that garments often come with – especially with retail e-commerce customers, where the packaging is one of the first things encountered.

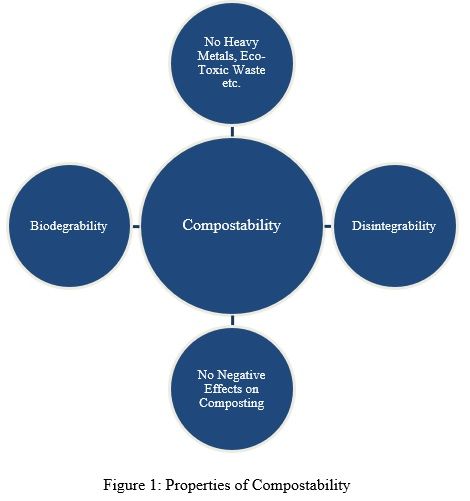

Each of the issues mentioned above is important for the definition of compostability. However, these are not sufficient alone. To be called compostable, a material must disintegrate during the composting cycle, and it must not cause any problem to the process, the final product or the compost (Degli-Innocenti, 2002). It is essential to understand that it is not enough to be biodegradable.

Composting is a beneficial waste management system, mainly where landfill sites are limited and that too among the more densely populated locations. The primary degradation mechanism of poly-lactic acid (PLA) is hydrolysis, catalysed by temperature, followed by the bacterial attack on the fragmented residues. In composting, the moisture and heat in the compost pile attack the PLA polymer chains, split them apart, and create smaller polymer fragments and lactic acid. Microorganisms in the compost piles then consume these produced polymers and acids for energy. This process involves bacteria and fungi for the degradation of PLA. The final result produces carbon dioxide, water, and some humus (D. W. Farrington, 2008).

The single-use culture has radically increased the amount of packaging waste a person creates daily, weekly, monthly and annually. Plastic, one of the most commonly used packaging materials across all industries, has an enormous adverse effect on the environment. It pollutes the natural landscapes and decomposes into microplastics which eventually end up in the oceans. This also affects marine biodiversity.

More and more businesses, organisations and academies are trying to find renewable and more sustainable replacements. The Sustainable Packaging Coalition has put forth a definition of sustainable packaging (Holding, 2019). According to this definition, the features of sustainable packaging are depicted in the figure below.

Brands are clamouring for alternatives due to this pressure. But there is a lack of information available about choices that can be made and action that can be taken. Several brands, like H&M, Stella McCartney, and Bestseller, have committed to shifting from all plastic packaging to reusable, recyclable or compostable. This commitment matches with the ones outlined by the UK plastics pact. The UK Plastic Pact encourages its signatories to achieve the goals by 2025. The signatories are also expected to reduce the single-use plastic packaging, recycle or compost 70 per cent of all plastic packaging, and include an average of 30 per cent recycled content across plastic packaging.

Nowadays, the products that we use in our daily life have a concise life span. However, the impacts of these products are long-lasting. It is essential to increase the circularity of the materials. This will reduce the quantity of single-use packaging.

Good packaging has some specific criteria to be met. It should suffice the purpose, protect the contents, optimise resources, and have a minimum carbon footprint. These can only be achieved through optimal design. The user-friendliness and the efficient material cycle are also crucial for environment-friendly packaging (Tiuttu, 2020).

However, despite its universality and apparent simplicity, it is a fairly complex system to maintain. Building a fully circular system for poly bags, or for any material, including alternatives to plastic, where everything is collected, recovered, and turned into something useful, is an ideal to strive for. But it is a daunting task one can only hope to achieve.

Comments