Introduction

The colour forecasting process is one of great complexity and very much an intuitive one. As yet, little information exists about its methodology, even though the process is considered to be a major driving force of the fashion and textile industry.

Colour forecasting is a fundamental part of a collective process known as fashion forecasting or trend prediction,where individuals or teams attempt to accurately forecast the colours, fabrics and styles of fashionable garments and accessories that consumers will purchase in the near future,approximately two years ahead.

The process of colour forecasting is basically one of collecting, evaluating, analysing and interpreting data to anticipate a range of colours desirable by the consumer, using a strong element of intuition, inspiration and creativity.

A dichotomy exists around opinions as to whether or not the forecaster predicts trends or merely creates them. Either way, a process has evolved over a period of time which has, in more recent decades, become increasingly complex. So much so that the secondary resource material readily available to the fashion student rarely offers more than a brief outline of the concept, the tools and the basic methodology involved in the colour and fashion forecasting process.

The process of colour and fashion forecasting has become a more integral part of the roles of many within the industry.Designers, range developers, sourcing personnel, buyers and merchandisers – and especially those who specialise in trend prediction for the purpose of selling their prediction packages to the industry – all use the current forecasting system. It is becoming increasingly important to clarify this process, both for those currently using the system and for the newcomer to forecasting, in order to improve forecasting.

While fashion forecasting incorporates all aspects of the design of garments and accessories, colour is a significant factor for the consumer when making a purchasing decision.

It is therefore considered that the colour forecasting process is a worthwhile subject to be investigated and further understood in its own right.

Colour forecasting is a specialist sector activity. This specialist sector is a service that makes use of the colour forecasting process. The information is compiled into trend prediction packages and sold to the fashion and textile industry.

Personnel within the industry use this information for direction,suggestion and as a source of inspiration. They then use the same process – or a very similar one – to develop their own company’s colour range.

Manufacturers use the prediction packages as one source of data together with other data collected. They then apply the colour forecasting process, or a version of it, to formulate their own seasonal colour ranges for their products to sell to the retail sector. The retailers may also subscribe to the colour forecasting services, purchasing the prediction packages to use as a source of inspiration to assist them to formulate their colour ranges

Consumers use a process of decision making when selecting a garment to purchase. Colour preferences are an extremely influential aspect taken into consideration. Successful sales reflect the effectiveness of the colour decisions that were made throughout the industry

The concept of forecasting came about through the development and growth of the fashion and textile industry to enable manufacturers to produce end products that would create sales on the high street. By the latter half of the twentieth century, a greater need had developed for more accurate information to be readily available to all sectors of the industry, from fibre, yarn and fabric manufacturers, through to the garment manufacturers and retailers – collectively known as the fashion and textile industry. As the industry eveloped globally and consumer lifestyles became more varied, so the process of collecting the necessary data for forecasting became increasingly diverse and complex.

Seasonal colours have become a powerful driving force of fashion today. The colour forecasting service was developed to fill a communication gap between the primary market manufacturers and the consumer, recognising the increasing complexities of forecasting with advances in marketing strategies. The service was established to deal with the problem of anticipating the colour demand/preferences of the consumer prior to the industry’s production time plan (lead time), thereby unburdening manufacturers of this process. While the concept of forecasting was originally for the primary market sector, selling information to the secondary and tertiary market sectors increased the revenue for the service sector and influenced a stronger consensus for the conviction of the colour stories. Whatever colours are finally predicted for a season and however these colours are promoted throughout the industry to the consumer, it is the decision to purchase made by the consumer that determines whether or not the predictions were accurate or valid.

Marketing may influence the consumer’s decision to buy; however, the colour choice is still the decision of the consumer, based upon their personal preferences.

As the fashion and textile industry is currently changing,retailers are showing evidence of relaying their observations and evaluation of the needs of the consumer back to the manufacturers, shifting the influence on colour direction from the manufacturer to the retailers. Developments in mass customization suggest that the current forecasting process is not as effective or successful as the industry would like. As the customer now is to some extent – and possibly always will be – a major driving force of fashion, their preferences are a key aspect for consideration.

It is difficult to find any book which clearly defines the stages of colour forecasting but a model of any process enables us to understand it more clearly. We will look at a model of the general practice currently employed throughout the fashion and textile industry and compare this with a proposed improved model. We do this using elements of a modelling tool known as soft systems methodology (SSM),widely employed in investigating human behaviour.

Soft systems thinking was a useful tool to use in investigating the colour forecasting industry and to develop two models.

The first of these models expresses the methodology as currently used and the second expresses what we consider to be an improved approach. These models were used to survey the UK fashion and textile industry in order to test their validity. Once analysed and interpreted, the survey results suggested that the models were easy to understand and that the response rate was good. The models were refined using feedback from the survey and consumer opinion was also tested, stressing the need to improve the current colour forecasting process

We have seen that colour forecasting provides a tool to help the fashion and textile industry make the correct colour choices for their products. However, it is evident that a potentially valuable source of information has not yet been fully exploited, that of market research to investigate and understand consumer colour preference, desire or need.

Colour forecasting provides:

an evaluation and analysis of the possible colour preferences of consumers for a season approximately two years ahead of the retail season, giving ample time to fit into the production schedules of the industry a service enabling the presentation and sale of this information to the fashion and textile industry

Colour forecasting is carried out worldwide by individuals working for specialist forecasting companies who will sell a limited colour story on a seasonal basis to the fashion and textile industry. The colour forecasting process and service thus promotes a selection of colours for a predetermined time period in the near future for all sectors of the fashion and textile industry. The forecasts predict colours through a complex mixture of intuition and analysis. The information is used by those responsible for the colour decisions of their company’s products.

Who uses the colour forecasting process?

Colour forecasters work in many different parts of the industry.

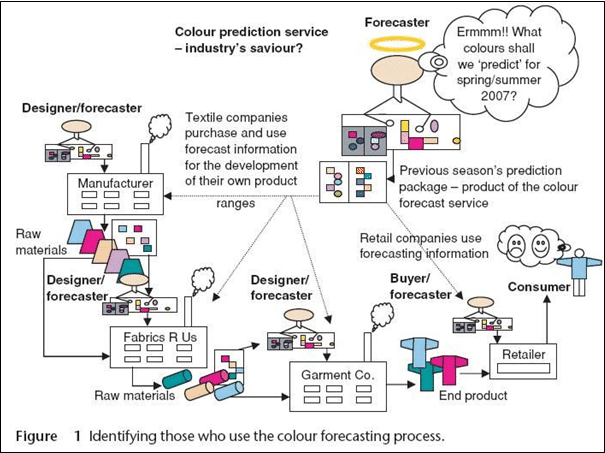

This is illustrated in Figure 1 which shows forecasters who work with the colour forecasting process from the Initial concept (the original colour forecasters) through to the consumer of the end product.

|

At the early stages of the process there are those who provide the service to the industry, known as the colour forecasting companies. Thereafter the information users become less and less involved, starting with the fibre, yarn and fabric producers, followed by the garment manufacturers, and finally the retailers. Often, designers and product buyers take on the role of forecasting as they are responsible for their company’s colour choices. Large companies generally have a team of people working together to compile their colour stories;smaller companies may have only one person responsible for this – usually the designer.

The first level of information users is that of the fibre and yarn manufacturers who supply the fabric manufacturers and knitwear companies. The fabric manufacturers supply the garment making industry, and both the knitwear companies and the garment manufacturers supply the retailers. The fibre and yarn manufacturers use colour forecasting information to help them to compile their own prediction packages in the form of shade cards with sales data usually influencing their choice of colour. The major companies’ colour teams all regularly attend national and international colour meetings.

Fabric and knitwear manufacturers use both colour forecasting information and fibre and yarn company shade cards to direct their colour choices, and this information is well disseminated via trade exhibitions. Garment manufacturers also utilise both forecasting information and shade cards;retailers will make use of forecasting information along with information gathered from trade fairs. Retailers may also use sales data, particularly large companies using EPOS (electronic point of sale) systems. No evidence has been found of collecting colour data, nor any indication of who could take on its analysis. This is a major source of information not presently exploited.

The consumer may be influenced by colour trends promoted through magazines and television but does not have access to the trade forecasting information. It is consumers,however, who prove the effectiveness of colour forecasting predictions by what they buy. The consumer is observed by the colour forecasters, hereby involving them in the process albeit without them realising it.

How colour forecasting is perceived ?

There are two basic views of the colour forecasting process:the positive and the negative. Those endorsing the positive view perceive the process as a tool used by a specialist service sector to provide accurate trend prediction information to the fashion and textile industry, enabling the user to anticipate accurately consumer colour preferences for a predetermined season in the near future. This allows the industry to manufacture desirably coloured products for the benefit of both the company and the consumer.

Those taking the more negative view see colour forecasting as a process used by a service sector to exploit the fashion and textile industry for financial benefit, and to dupe the general public by its attempts to direct consumer preferences with clever marketing. This negative interpretation is perhaps extreme but may be happening by default, despite the best intentions of the forecasters. A high volume of sales on the high street will confirm the forecasters’ ability for getting it right, instilling confidence in the service. Low sales however will weaken the credibility of the forecast predictions, generating a lack of confidence in both the service and the process.

In reality, it is probably a combination of the two perspectives that prevails. The tangible, objective tools instill confidence, while the less understood, subjective ones create suspicion. Good marketing engenders optimism but a low volume of sales on the high street leads to pessimism. If the ‘softer’ elements of the process were better understood and the forecasting process as a whole demonstrated a higher success rate, forecasters would be perceived as beneficial to the industry. Colour forecasting may thus be seen as a process that has potential to assist the fashion and textile industry to thrive but is as yet little understood, so remains underdeveloped and its value consequently underestimated.

Two further points for consideration are those of consumer lifestyles and mass customisation and how they add to the perception of trend forecasting. Consumer lifestyles are much investigated and their significance now recognised as a key influencer of marketing. Companies base their product range on customer profiles created from lifestyle information. But what of colour preferences? Consumers can only choose to buy or not buy the products on offer at that moment in time, expressing their acceptance of the products offered.If lifestyles are so important to marketing, why is colour preference data not felt to be beneficial? Why is the industry still so reliant upon the forecasters’ anticipations of colour acceptance? Mass customisation is the large-scale manufacturing of individual consumer products. Whether or not this approach is viable is not the issue but it does suggest that the industry may not be completely satisfied that the present forecasting service is as accurate in its predictions as it could be. Accuracy is crucial to the survival of the industry.

If lifestyles are so important to marketing, why is colour preference data not felt to be beneficial? Why is the industry still so reliant upon the forecasters’ anticipations of colour acceptance? Mass customisation is the large-scale manufacturing of individual consumer products. Whether or not this approach is viable is not the issue but it does suggest that the industry may not be completely satisfied that the present forecasting service is as accurate in its predictions as it could be. Accuracy is crucial to the survival of the industry.

The responsibility for colour direction The onus for the direction of colour initially rested with the primary market sector; i.e. the fibre, yarn and fabric manufacturers.

They produce the colours of the raw materials that the rest of the fashion and textile industry use. Yet the retailers clearly have more access to information on consumer buying behaviour and selection preferences through sales data, observation and feedback communicated from the shop floor.

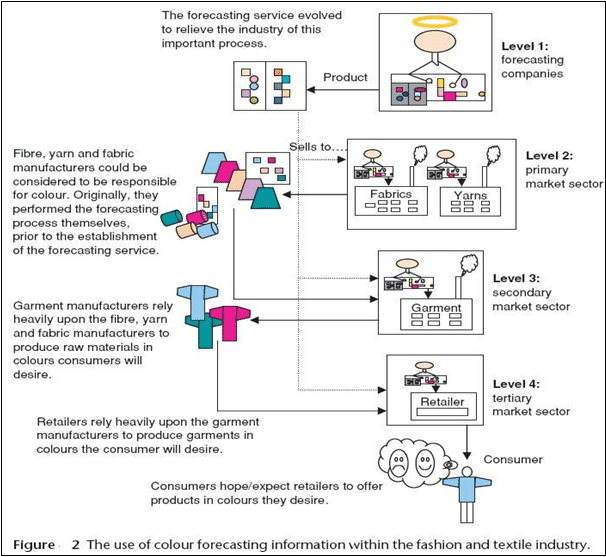

Four areas of the industry are illustrated in Figure 2, referred to as Levels 1 to 4: the forecasting sector; the fibre, fabric and yarn manufacturers; the garment manufacturers; and Level 4,the retailers, identifying the usage of colour forecasting information at the different production areas of the industry.

Historically, the forecasting sector was incorporated within the manufacturing sector, until forecasting companies were established and relieved the primary market sector of the growing complexities of the forecasting process.

The responsibility for colour direction is now beginning to change as the current system of manufacturing and retailing is restructured. Many fashion manufacturing companies are producing garment designs and specifications around the table of their design room, along with the buyers of the top high street retail stores. Production of the garments is undertaken by CMT (cut, make and trim) factories, and the fashion company may then screen print the surface design onto the garments according to their clients’ requirements.

The specifications, including the colour range, are agreed by both parties and though the initial colours are determined by the retail sector, the fashion company advises on any technical problems they may encounter when working with particular colours on certain fabrics or fibres.

The system previously in operation has now changed in some areas of the industry. Retailers are becoming more aware of the consumer, observing and testing through instore trials in order to anticipate more accurately preferences within their own market niche. They then dictate their requirements back to the manufacturing sector, thereby shifting the onus for colour direction. If only large retailing companies existed, then the responsibility for colour would be entirely with the retailers. At present both systems operate concurrently, as independent or sole trading shops do not have the clout to demand their requirements from the manufacturers.

Instead, they use wholesalers who act as middlemen between retailer and manufacturer. This increases the cost of products to the independent retailer, disadvantaging them further. However, even independent stores operate some kind of forecasting method in their efforts to supply garments that their customers will want to buy. Some kind of decisionmaking process has to be used to make informed choices on colour for stock, unless garments are to be selected totally randomly, or intuitively. Even this apparently obscure process of selection must be based on some sort of identifiable methodology using thought, reasoning processes and decision-making.

We found that many dye houses are working on a commission basis, dyeing to customer specifications, usually supplying only the larger companies. Also, some yarn merchants buy stock without consideration of their customers’ needs, on the assumption that the yarns will sell eventually. Such merchants are often riven by low price opportunities (stock clearance sales) more than by planned stock purchasing.

These sales-driven rather than market-driven businesses are still supplying the independent retailers through manufacturers and wholesalers. But would it not make better business sense to stock to demand? Also, chances of repeat orders are hindered when the yarn eventually sells out some years later as it is then difficult to match the dyelot. Some companies appear not to carry out any kind of forecasting.

The current colour forecasting process Colour forecasting aims to evaluate accurately the moods and buying behaviour of consumers; it collects colour data,analysing and interpreting it intuitively. The process depicts the possibilities and anticipates the direction of colour, as well as assessing the rate of change seasonally in order to establish what timing of such changes is acceptable to the consumer. The seasonal colour stories indicate hue, value and intensity and are heavily promoted throughout the industry.

While these stories are thought important to the generation of high street sales, they can also set limitations, dissuading individual companies from using their intuition and feelings for colour direction based on their own sales data.

However, those with knowledge of the process are reluctant to divulge any indepth information either because of commercial secrecy or because they find it difficult to explain the system in detail.

The colour forecasting process involves the series of activities including data sourcing and collection; analysis and evaluation; interpretation and presentation.

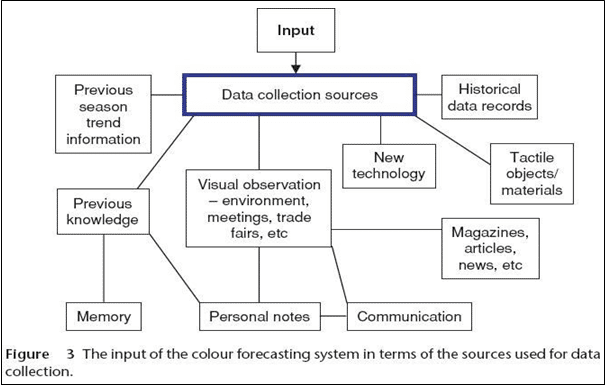

The many varied sources used by the colour forecaster create a database, which can be described as the input of the system,as shown in Figure 3.

|

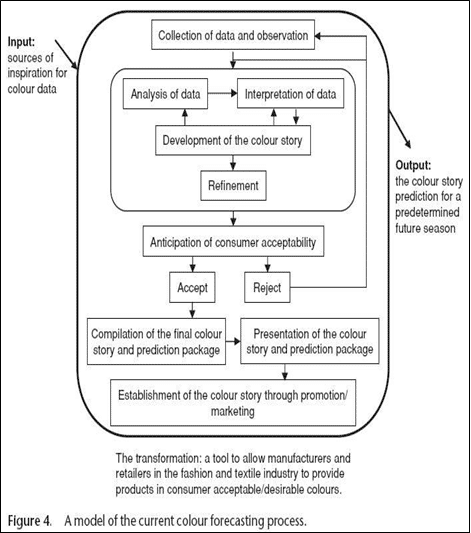

The final result is referred to as the output of the system and can either be viewed as a colour story or as a trend prediction package. The stage between the input and output is that of transformation, i.e. what takes place in order to change the data from source into the final result.

This transformation stage is essentially the process of colour forecasting as a tool for the application of seasonal trends for the fashion and textile industry. The first activity in the compilation of a colour story is collecting the data.

Hard data is assessable and recorded, such as sweet wrappers and fabric samples; soft data remains in the forecaster’s memory, employing awareness and observation skills. The information is then analysed using a process of assessment and elimination, employing awareness and observation skills.The information is then analysed using a process of assessment and elimination,employing intuitive skills as well as thought,decision and reasoning processes which we will term soft skills.

The information is then interpreted, giving it meaning, using these same soft skills and so the colour story develops, via a process of assessment,comparison, selection, exploration and experimentation.

This development continues until the forecaster is satisfied with the result. The colour story is then refined through a process of elimination, again involving the soft skills. The current colour forecasting process anticipates consumer acceptability,with the forecaster accepting or rejecting certain colours

If colours are rejected then the process can begin again at any point, even as far back as collecting further data. If the colour story is accepted, then a final colour story is completed through to packaging for presentation. Predictions are then established through promotion and marketing. A model of the current colour forecasting process is shown in Figure 4

|

This model was validated by testing a large sample of personnel within the manufacturing, retail and specialist sectors of the fashion and textile industry involved in forecasting.

Over 80% agreed that the model was a close representation of the current colour forecasting process. The model was subsequently improved by taking into account feedback from the industry. Those using a different methodology were identified as independent retailers who claimed not to use a forecasting process.

Testing the model of the current forecasting process

The accuracy of any prediction is validated through sales on the high street and to test the effectiveness of the current colour forecasting process, we asked the general public their opinions. We found that only half were satisfied with the colour range available to them.

Forecasters aim to satisfy 80% of the general public with their predictions but the current colour forecasting process is not providing the level of satisfaction needed by the manufacturing and retailing sectors of the industry. The process would benefit from some improvement to create more sales on the high street and offer more security for manufacturers. Feedback indicated that the colour choice is too narrow as most high street stores are promoting the same colour stories. On the whole, this survey indicated a high percentage of the general public would welcome a wider colour selection. Eighty-three percent said that colour would or had influenced their purchase.

Colour is a strong influence when purchasing fashion garments and sometimes the fabric, particularly specialist fabrics such as denim and suede, will influence a purchase. Also, style and fabric sometimes persuade the consumer to purchase even though an alternative colour would have been preferred.

Staple or neutral colours (such as white, black, cream, beige) are more likely to be bought as a compromise to preferred colours than fashion colours would be. These staple colours are therefore considered by the industry as safe colours.

Fashion colours or fad colours require more skill on the part of the forecasters to anticipate their level of acceptance and by which segment of the consumer market. It is the forecasting of these colours that would particularly benefit from an improved process.

The missing link

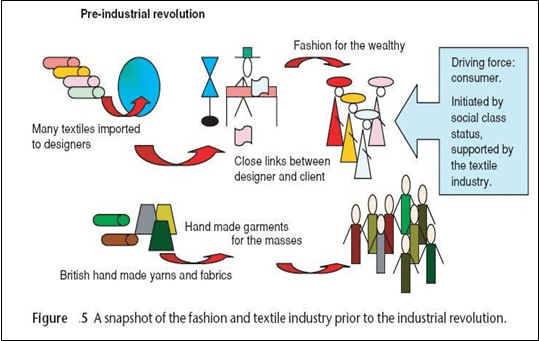

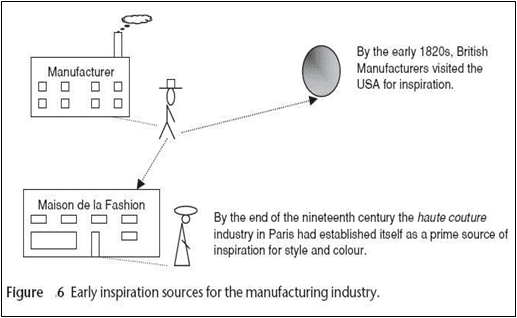

The consumer has been identified as being one of the prime driving forces of fashion. Before the industrial revolution,designers had close professional relationships with their clients (those able to afford fashion) as shown in Figure 5. As the textile industry thrived, new sources of inspiration were sought by manufacturers, demonstrating an early demand for forecasting, shown in Figure 6

|

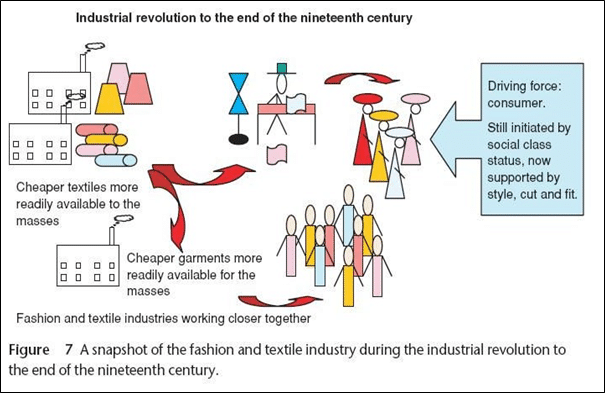

While couture designers maintained their links with clients, the industry did not. This is illustrated in Figure 7.

|

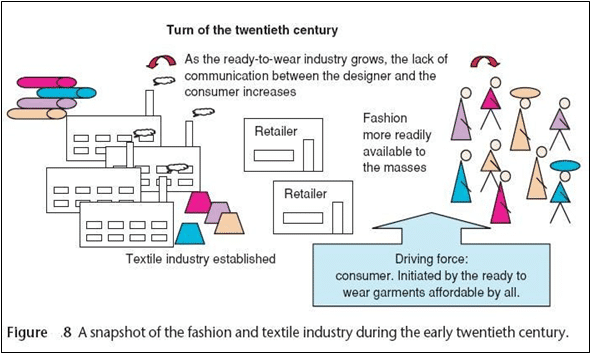

By the twentieth century, direct links between consumers and designers were very few, only existing in the haute coutureindustry (see Figure 8). As designers within the industry do not work on a one-to-one basis with clients, there is no direct link between the industry and the consumer. As this lack of communication increases, manufacturers become less informed of consumer needs. This became recognised and by 1930, a small number of forecasting companies were established in Britain following in the footsteps of the USA.

By the early 1930s seasonal colour palettes were emerging as an important directive for trend information. This development seemed to disappear over the subsequent 40 years,possibly with the demise of The British Colour Council, the originator of the concept

The notion of fashion being consumer directed became increasingly evident and important. More forecasting companies were established during the 1960s and 1970s and marketing strategies became crucial for company survival. As the recession lifted, consumer lifestyles became ever more varied. Marketing techniques rose to this challenge and the industry’s need for precise consumer colour trend information increased, particularly within the primary market sector – the fibre, yarn and fabric manufacturers

Following the lead of the fashion company Next, colour established itself as a key marketing strategy and a more important driving force of fashion. Forty years after The British Colour Council initiated the seasonal colour it now took a key role in forecasting. However, forecasters may still be guilty of influencing colour direction as opposed to anticipating it.

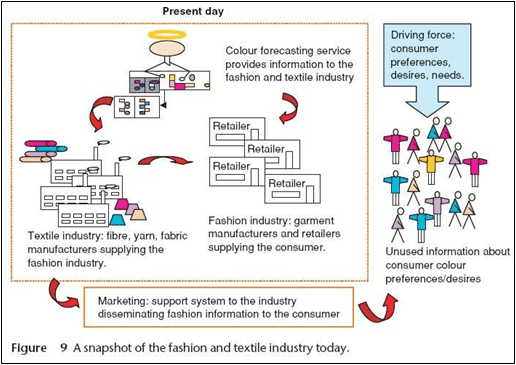

Figure 9 presents a snapshot of the present state of the industry in relation to the consumer. Is consumer demand for colour really sought and recognised? Are the forecasters still assuming our demands Preferences? Or are they deliberately trying to direct them?

Judging by the end-of-season sales on the high street, consumers’needs are still not being met successfully. This may be due to the fact that observations of consumer desire reflect colours already available; one cannot observe the general public wearing colours not available to purchase.

While the driving force of fashion has always been the consumer, the economy of the industry also has a bearing upon fashion – or at least upon the rate of change of fashion.

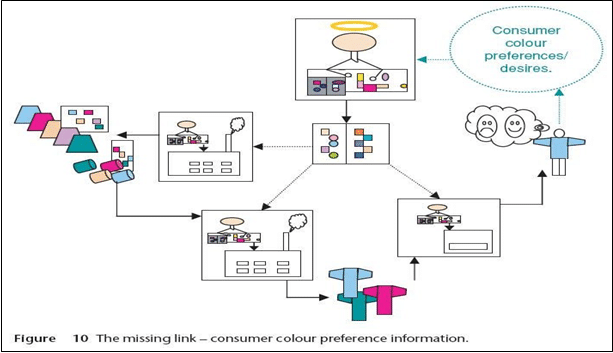

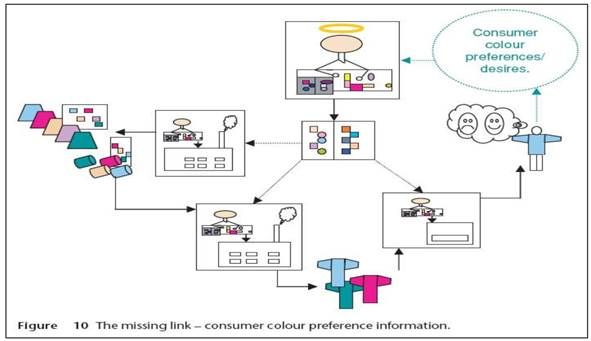

Due to the structure of production costs, colour is a relatively easily changeable factor. Colour has therefore become a very important element of the driving force as well as a powerful marketing aide. Sales have become heavily dependent upon seasonal colour stories and colour therefore plays a substantial role in the fashion and textile industry. The consumer influences the validation of colour forecast predictions, and is also a source of information through market research,though this area appears to still be relatively unexplored(see Figure 10)

Due to the structure of production costs, colour is a relatively easily changeable factor. Colour has therefore become a very important element of the driving force as well as a powerful marketing aide. Sales have become heavily dependent upon seasonal colour stories and colour therefore plays a substantial role in the fashion and textile industry. The consumer influences the validation of colour forecast predictions, and is also a source of information through market research,though this area appears to still be relatively unexplored(see Figure 10)

Creating a better model for the colour forecasting process

Colour forecasting can be viewed both as a service and as a process. The service is the marketing function of the prediction packages, the product of the colour forecasting process.The process is used to produce and promote a selection of colours. The industry uses the prediction packages to assist in their colour decisions, in the hope that their resulting products will achieve optimum sales by meeting the desires, needs and preferences of the consumer.

.

Ideally, the consumer should benefit from the availability of desirably coloured products on the high street. The level of benefit here is the real crux of the matter under consideration and determines the effectiveness of the whole process

The higher the level of benefit for the consumer, the higher the volume of sales on the high street (subject to disposable income and state of the economy). The accuracy of anticipating the consumer’s colour preferences or demands determines how beneficial the service is to the consumer and to the fashion and textile industry. However, beneficiaries of the colour forecasting process can also be seen as its victims if the efficiency of the system is in question, and forecasts prove false.

The industry buys the rediction packages from the specialist forecasting sector to achieve a high volume of sales directed by consumer satisfaction. To make sure that the colour range is acceptable – or better still, desirable – to the consumer, testing the market is clearly preferable to anticipating it.

We found that almost 70% of respondents involved with the colour forecasting process felt that the current system could or should be improved to benefit both the fashion and textile industry and the consumer. More than half questioned were from the retail sector, indicating that this sector is highly conscious of consumer satisfaction, having a more direct link with the consumer.

Another reason may be the apparent shift in responsibility for colour direction, as previously discussed

The improved process model

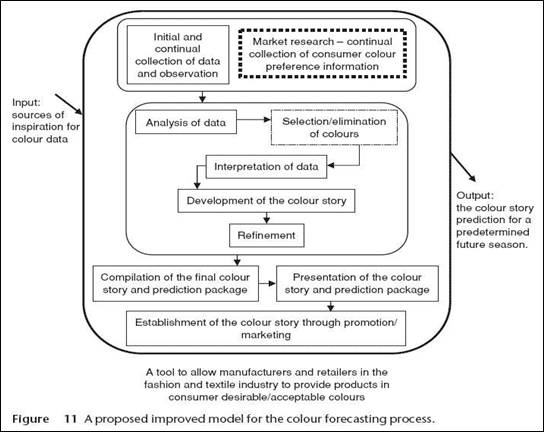

A proposed improved model for colour forecasting is shown in Figure 11. As consumer preference data gathered in the shops would be more accurate than what the current system offers, the colour palette as a whole should not, theoretically,be rejected as much as in the current model.

|

Individual colours may be eliminated while developing the final colour palette. We can therefore exclude the accept and reject stages of the current model (shown in Figure 4), used to anticipate consumer cceptability, in favour of a stage of selection and elimination which would take place between the analysis and interpretation stages much earlier in the process, therefore saving time between the refinement of the colour story and its final compilation. The proposed improved system would be used to collect,on a continual basis, data on colours not currently offered, as well as aiding assessment of the changing levels of acceptance of current colours offered on the high street.

Alternatively, this could be a separate source of data incorporated into the input of the model if the information was collected and analysed by a third party, such as a market research consultancy.

This could start another new sector, in the same way that the specialist forecasting sector was formed in the twentieth century. A device could be designed and sited in stores for consumers to interact with. The analysis from this would be undertaken by the designers and/or buyers currently using colour forecasting

What forecasters said about the improved model ?

To validate this new model we asked the respondents for their views. Almost 70% of these in retailing agreed that their company would benefit from the improved system; almost 50% in manufacturing, and more than 80% of forecasters in the specialist sector also agreed.

Those involved in the initial process would welcome a database of hard information to assist them develop their colour stories using stronger objective tools; the retailers would also appreciate this more tangible Input

The manufacturers would find themselves more dictated to and become less proactive as the responsibility for colour direction changes.This model does not suggest any need for consumers to understand the process of colour forecasting; they are simply asked to contribute to the data collection by indicating their colour preferences, or stating which colours are missing.

It can be argued that consumers do not know what they want until they see it and marketing plays a key role to exposing them to something new in readiness for its acceptance.

This theory can be incorporated into the improved model, as a series of colours would constantly be shown to those consumers interacting with the market research device.

There was slight concern by the industry that the methodology would no longer be forecasting if the consumers are given what they want. However, the colour palette to be tested has to be predicted initially and the testing stage would be used to verify its compilation.

A misconception of consumer preferences emerged from our survey. Some retailers give consideration to previous seasons’ best sellers and see this as recognising consumer preferences. But as consumers can only buy what is available at the time, sales data gives no more than a snapshot of purchases in the present or past; it cannot indicate preferences for colours not currently on offer.

In-store trials,where the general public is asked to give feedback on colour preferences, are used by some of the larger retailers though again obtaining feedback only on acceptability of selected colours. However, as this is a costly process it is not viable for the smaller retailers.

A comment of particular interest was made by personnel from the specialist sector that it is sometimes possible to base a season’s new stock on a previous season’s best sellers. While the range would not offer the consumer anything new interms of colour, it would support the prime role of colour preference data and its application to the colour story.

Though again, present colour preference data will not highlight potential new colours for the range

One respondent commented that an element of surprise and beauty is always required of a range. Surely this element should be incorporated into the application of colour and the style of the end products. Also, we are not dismissing the importance of intuition, which will always exist

It should be remembered that colour is an important influential factor of the consumer’s buying behaviour, but other aspects are also influential and important. It is the role of the designer and of the buyer to take these aspects into consideration. The garment as a whole should reflect something new, not the colour alone.

There was an encouragingly high level of positive feedback,including suggestions that using colour preference data could save a great deal of time for the system user. Consumer opinions were recognised as beneficial to the retail industry and including the consumer in the process was seen as sending out a positive message and making the consumer feel valued and respected. It was felt that consumer preference information would help to diminish the influence of the shop buyer’s preferences in ranges.

Many respondents believed the improved model was of interest and if achievable at speed, could supply the retail sector with suitably concise forecasts

Other respondents were concerned that the proposed model could result in a rigid colour palette, unchanged from season to season. We do not consider this to be likely, as each retailer would be working with data obtained by their own customers, or potential customers. The information would therefore be unique to each store, producing different ranges in different stores, depending on the target market customer.

This would result in more choice for the consumer along the high street as a whole. Retailers with more than one outlet would benefit from being able to regulate the different levels of colour acceptance in different store locations across the country – as well as across the world

Some respondents felt the model was worth testing as it may lead to a return of style rivalry instead of the present price rivalry. Currently the consumer may benefit monetarily but at the expense of quality; in other words, you get what you pay for.

Style rivalry however, stimulates quality at good value for money; this may be the key to the thriving manufacturing industry that the western world once had, making them strongly competitive once more

There was positive feedback for the development of a method to capture consumer preference data quickly and to constantly monitor changes of taste

Marketing was highlighted as a possible way of enabling the consumer to continually influence colour ranges before products went on the shelves in the high street.

Retailers are becoming more aware of consumers’ needs and desires through market segmentation and target market profiling developed to assist the retailer to stock in accordance with the requirements of their average customer.

The target market customer profile is fictitious but is based upon market research, which includes demographical information and lifestyle analysis.

The proposed new colour forecasting model would be highly beneficial to retailers, re-establishing the lost links with the consumer since the growth of the industry.

The missing link is that of consumer colour preference.

The survey conducted in order to validate the current model and to test the proposed improved model with personnel within the industry suggested that a high percentage was in favour of improving the current colour forecasting system and in particular, that the inclusion of consumer colour preference data would be advantageous to the retail sector.

Summary

A process for forecasting colour has evolved and while this process may vary slightly from user to user (and some personnel appear to be unaware of using a system at all), the model of the current process discussed in this chapter is representative of how it works throughout the fashion and textile industry.

However, just because a process is widely adopted does not mean it is working to its optimum level, nor that mprovements or updates to the system should not be considered.

In fact, fashion and consumer desire is an ever moving and changing energy so it does not make sense for the colour forecasting process to be stagnant in its approach to trend prediction.

As our survey showed, the current process is not attaining the level of satisfaction on the high street that forecasters aim for. We have looked at one way in which the present process could be improved. It is not suggested that this is the only way, nor that no other improvements could be identified,tested and applied.

The development of trend prediction should be an ongoing process, like fashion itself. The recognition of the current shift of responsibility for the direction of colour within the industry demonstrates the need to remain sensitive to change.

In this article we have discussed the current forecasting process in greater depth through models and looked at one way of improving the process for the benefit of both the industry and the consumer.

Comments