Spinning mills in India are facing a double whammy. On the one hand, cotton prices are at an all-time high, and on the other, stockpiles of yarn are rising by the day. As lockdowns continue to be imposed or extended in one state after another, spinning mills feel stifled.

The situation reached alarming proportions in April itself, prompting the South Indian Spinners Association (SISPA) to write to Prime Minister Narendra Modi, minister for textiles Smriti Irani and minister for micro, small and medium enterprises Nitin Gadkari on April 26.

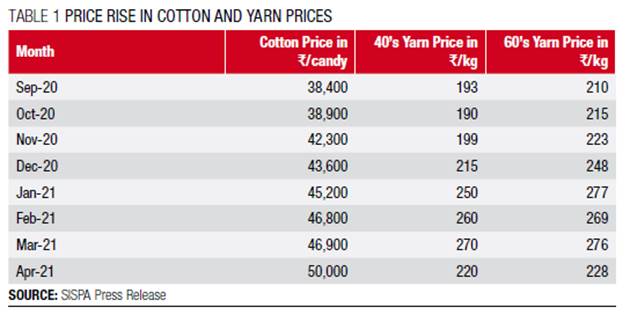

One of the things presented in the letter was a tabulation of cotton prices in India over the past few months and the corresponding prices of two categories of yarn. The table indicated that while the cotton prices were at an all-time high, the selling prices of yarn were quite discounted. Apart from this, mills were facing various other problems which jacked up their production cost. These included running mills at 50–60 per cent utilisation, besides an increase in the costs of packaging material, spares, transport, labour and diesel.

The data collected from 400 units indicated that most mills were unable to sell cotton yarn, polyester-cotton yarn, polyester-viscose yarn and polyester yarn of all counts. Stocks have been piling up since April 1. Besides, there are a large number of mills in financial throes and running huge debts for ten years now. The pandemic crisis has only worsened their situation.

Another point mentioned in the letter was the allegation of the Apparel Export Promotion Council (AEPC) that spinning mills were holding the yarn and working as a cartel over the prices of yarn. It contended that major centres like Mumbai, Bhiwandi, Ichalkaranji, Malegaon, Surat, Kolkata and Erode were unable to procure yarn as the demand itself was very poor.

The letter, therefore, urged the Indian government to facilitate industries to liquidate their yarn stock, and shield MSME units from false propaganda.

The SISPA Situation

According to Vyankatesh Prabhu, a manager at SISPA, there are around 3,000 spinning mills in India. SISPA, with its office in Coimbatore, represents the 400 spinners of South India. It supports them in representing them to the state and Central governments, and provides quality testing support.

Jagdish Chander, SISPA vicepresident, says the association’s members are mostly located in Tamil Nadu and fall under the MSME category. Because of the lockdowns in various states and the overall pandemic situation, no one has been buying yarn since April 1, resulting in a pile-up of stocks at the mills. Workers at these units mainly hail from Odisha, West Bengal and Bihar. Over fears of fresh lockdowns being imposed at any moment, many of the workers have returned to their home states. As a result, many mills have been working at half capacity, thereby increasing the operating costs.

Among the things that the SISPA letter had emphasised was that the current market prices of yarn are very low. When this is seen in the backdrop of cotton prices being at an all-time high, it becomes a losing proposition for mill owners. While these units had already been struggling in the wake of continuing recession, rising prices of raw materials and labour migration, most of the problems have been compounded by the non-uniformity of government policies for the textile industry during the pandemic and lockdowns throughout the country.

The situation elsewhere

According to Gautam Dhamsania, secretary of the Spinners Association of Gujarat, “There are over 100 spinning mills in the state, primarily in Ahmedabad, Rajkot, Surendranagar, Jamnagar and Amreli. All are either medium or small industries. Spinning mills in the state produce about half for the domestic market, while the rest is exported. The exports segment is not facing any major problem as yet, but the domestic market is down. Exports too may be hot soon. Since millers unable to sell in the domestic market have been eyeing exports, this segment is becoming very competitive.

In many units, either the workers themselves or their family members have tested positive for covid-19. Therefore, absenteeism has been on the rise. Fear too has been keeping employees away. With many migrant workers returning to their home states/cities, many of the units are working at an 80 per cent capacity and are in any case yet to recover from the effects of Lockdown 1.0 last year. “It looks as if trouble is increasing day by day. We are also facing problems due to the high prices of cotton in the market,” rues Dhamsania.

The ground situation is not very different in Panipat, Haryana where over 500 mills are located. These mills mostly produce woollen yarn that is subsequently used for production of bedsheets, carpets, blankets and several other products.

Vishal Gupta owns a spinning mill in Panipat, which is currently working at only 10 per cent of its production capacity because of several reasons. The first is that there is practically no demand.

Gupta sells his products to several states in the country. Because of the lockdowns in several states, there is no movement of his goods. Gupta’s company exports as well, but the lockdowns in Nepal and Sri Lanka have ensured that exports too have come to a halt. To make matters worse, interest premiums on bank loans have been mounting.

Gupta’s unit has an 11 KVA connection. In spite of most machines not working for the better part of the day, he still has to pay for the electricity costs. Gupta wants the government to step in and offer interest-free periods on bank loans. It should also waive off power charges for a while.

The labour-related issues too are the same. Most workers from Uttar Pradesh and Bihar have returned. The yarn from Gupta’s mill was earlier purchased by other manufacturing units for producing carpets and bedsheets, among others. Since workers in these industries too have migrated back, these producers are not buying the goods either.

The stockpile due to zero demand wore heavily on Ankur Gupta of Ambey Spinning Mills, which mostly sells products to blanket makers in Haryana. Gupta had to ultimately sell products at heavily discounted prices and incurred a huge loss. Gupta employs workers from Bihar, most of who went back over lockdown apprehensions. The factory is now running on a single shift, thereby hiking up the production cost even though the fixed cost remains the same at 50 per cent production. Gupta owned another unit for polyester yarn that was closed down. Losses had been mounting since Lockdown 1.0 and the promoters had no idea about how to recover them.

The problems with Ripple Patel, promoter of a spinning mill in western India, are slightly different. There is no pile-up of inventory or raw material, and the mill has been running at a low capacity since most workers have returned home. Patel, whose spinning mill is located on the Rajkot-Jamnagar highway, has pending orders which cannot be shipped due to logistics issues. He is also unable to get container bookings to sell finished products to many countries. Patel feels if the government allows industrial transportation during lockdown that would reasonably ease down issues for manufacturing units. Even if transportation is allowed to run during the designated timeframes only, it could still be highly beneficial for manufacturers.

Proposed solutions

Chander is urging the Centre to form a countrywide uniform policy for the textiles industry. If the decision is left to individual state governments, each would have a different policy. The textiles business is scattered and lots of states are interconnected in the business. If one state has a lockdown right now and another the next month, business will suffer during both months.

Moreover, workers are not clear about lockdowns and industry policies because of which many of them returned early and others followed. If there is a countrywide uniform policy of keeping industry open and working at 50 per cent capacity irrespective of a lockdown, “our work would be much more predictable. Also, government bodies should refrain from false propaganda during these trying times. The government should help us to clear the pile-up of inventories,” he contends.

According to Dhamsania, the government has policies like Remission of Duties and Taxes on Export Products (RoDTEP) and Merchandise Exports from India Scheme (MEIS) as incentives for industry owners. However, spinning mills are not included in these. The government should expand the net for these policies so that the spinning mills are also benefitted. While Patel calls for industrial transportation to continue during lockdown, Vishal Gupta wants the government to consider a moratorium on loan interest and exemption in electricity charges for industrial units.

This article was first published in the June 2021 edition of the print magazine.

Comments