Second-hand clothing is expected to become a major trend in the coming years as consumers increasingly bought used clothing during the last few years. Consumers were primarily attracted to the second-hand clothing market because of the reasonable pricing and more recently because of being conscious of the impact of fast fashion. In the US, the second-hand clothing market currently (2021) operates almost equally through thrift shops & charities and resale through various online platforms and was valued at almost $36 billion at the end of 2021. By 2025, its resale market is expected to grow much faster than thrift and charities in the US (total valued at $77 billion), considering two things – more Gen Z consumers move to second-hand clothing, and resale online platforms increase their reach. The market in Europe for second-hand clothes was estimated at around €13 billion in 2019, is now valued at close to €34 billion at the end of 2021 and is expected to see much stronger growth.

Selling second-hand or worn clothing is not new. The informal economy for a very long time provided avenues to supply used clothes from sellers to interested buyers. On the other hand, there have always been individuals who preferred to buy second-hand clothes primarily due to their reasonable prices, particularly for those who couldn’t afford to frequently buy new clothes, until very recently. The sustainable aspect of this market has also been very recent. However, it is not hard to imagine that the second-hand clothing market depends on the already existing produce and its future growth in fresh produce. The question worth asking then is whether ‘resale-at-scale’ provides a valuable solution to existing problems of waste in the fashion industry. Not that this question hasn’t been asked before. It has perhaps been answered variedly by many experts who would have a much greater understanding of the industry. But the answer is surely not definite and straightforward.

One very problematic aspect of expecting a booming second-hand clothing market (as revealed by some studies conducted recently) is also to presume a booming supply of new clothes in the market. Essentially, resale platforms rely heavily on individual sellers to sell their used clothing. Major fashion brands have either launched their resale platforms or tied up with existing online platforms to get their consumers to sell used clothes. While it is noble to provide a platform to sell used clothes which would have otherwise gone to the dumps, this approach doesn’t stop fashion brands from producing new clothes at the current rate. Also, fashion brands with their resale platforms implicitly provide greater incentives if customers choose to buy more clothing instead of just taking the money from the sale.

Similarly, independent resale platforms where individual sellers list their used clothing directly, the point of concern is whether all clothes attract a buyer and after how many uses, would a piece of garment not receive buyers. If sellers only sold those clothes which become unfashionable for them, and buyers only buy what they considered relatively new in fashion, isn’t it highly likely that many of the garments won’t ever attract buyers? As increasingly more clothes come into resale, the amount of unsold inventory might go up even further, which would eventually go to waste. A more cynical argument forwarded in this context is that with an organised resale market in place, fast fashion brands might have no incentives to cut back on their production rates.

A very strong argument that has helped aggressively boost the used clothing market is that a piece of used garment reduces demand for a similar new garment and hence prevents the resource use for its production. Yes, that is perhaps the truest of them all. But even then, the market itself doesn’t change consumer’s preference to always seek more. In contrast to that, there are now more options available to a consumer, with an even greater disparity in pricing. The stigma of used clothing may have been overcome in the US at least, but that has not curbed the inclination to always keep buying.

Do economic conditions determine the demand for used clothing?

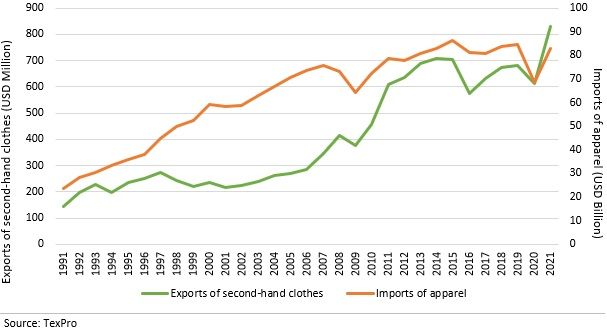

Fashion is also very cyclical like many other sectors in the economy, and fashion trends depend heavily on how the broader economy is performing, or at least the perception of it. Preference for used clothing would depend on it even more. It has been recorded historically post several periods of the economic recession that spending on clothing is reduced drastically since individual’s finances are hit severely. This is the time when they have historically preferred to buy more used clothing. Figure 2 shows how during the period of the boom (2002-06), US exports of worn clothing stagnated while its imports of apparel kept riding higher. It is only when the growth slowed down in 2007 and during and after the recession in 2008-09, that these exports shot up again. Exports of used clothing from the US remained fairly high during the decade 2010-2019.

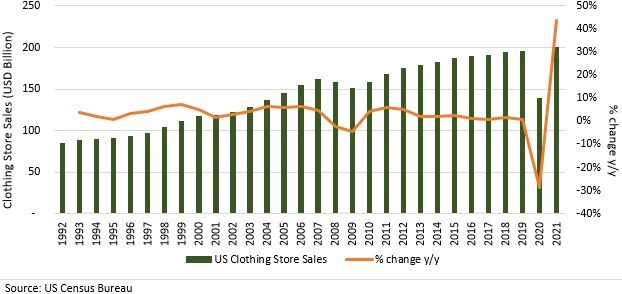

During and perhaps sometime after the Global Financial Crisis in 2008-09 consumers either spent less on clothing or spent more on second-hand clothes or discount retailers, giving more fuel to the era of fast fashion. The discount trend has stuck so much with the consumers that it has continued since then. Evidently, then there has been a slump in overall spending on clothing (Figure 1), especially in the US where economic growth in the last decade remained fairly muted. This is evident from the growth in sales of clothing stores in the US during the decade 2011-19 relative to the previous two decades (accounting for the two recession years in 2001-10). Clothing sales (in USD terms) during 2011-19 grew only by an average of 2.4 per cent as compared to 4.6 per cent average growth during 2001-10 (counting out 2008 and 2009).

Figure 1: Clothing store sales in the US

This could imply three things–1) overall volume demand for clothing didn’t grow as much in the last decade compared to previous decades, 2) clothing demand increased in volume, but consumers moved to buy cheaper clothes (fast fashion) or 3) consumers bought more used clothes during the last decade than they did ever. All three are partially true. In times of duress, it’s not that individuals don’t shop for clothes, but shop for bargains. Individuals would save money even where they didn’t earlier. The appeal of used clothes (very reasonably priced, high-quality goods) becomes even larger in these times. The supply of used clothes also increases during times of economic stress, as individuals scramble to get cash from anywhere possible. It is not without reason that the resale market is known to be recession-proof. The Association of Resale Professionals in the US put out a press release in July 2015, that precisely mentions this aspect of the resale fashion market.1

But as the impact of the pandemic waned, the demand for new clothes jumped up significantly in 2021 to surpass pre-pandemic levels. Simultaneously, demand for pre-owned clothing went up on resale platforms, that are closer in nature to trendy e-commerce platforms than their more conventional versions, the thrift shops. US total imports of apparel and exports of worn clothing both shot up in 2021, indicating that as trendy as buying second-hand clothes became, more and more volumes of clothing flooded the market, and more and more clothing perhaps went to landfills. It is not very hard to assume that the volumes of used clothes exported from the US would be much higher than the numbers sold online, while the dollar value of the former would understandably be lower.

From an economic perspective, therefore, it is perhaps hard to say what will happen to the demand for used clothing going forward. Although, if the supply of new clothing continues to see similar growth, the used market will also see a strong uptick. The presence of online resale platforms has surely ensured that individuals buy and sell used clothing irrespective of income levels.

Figure 2: Clothing imports and exports of worn clothing – United States

Can used clothing demand lead to an increase in the supply of new clothes?

But assuming that resale platforms do grow as they promise, the real question is how close it is to solve the issue of waste. On the face of it, there are certain aspects to the recent hike in the preference for second-hand clothing that may not hint at the sustainability side of this market. Many re-sellers on the online resale platforms particularly go shopping in thrift shops to pick trendy pieces to be sold for hefty prices later on. The fact that prices of used clothing on resale platforms are dramatically higher than those available in thrift shops and search costs are lower, attracted many to sell their old designer clothes for quick and good cash. There are largely sold as rarity, a piece of great expected value available cheap. Going by the label ‘vintage’, the used clothes market on online platforms is now flooded with similar pieces of clothing but priced very differently.

The key aspect here is the utility of buying used clothes. Generally, the second-hand clothing market is for individuals who are constrained to buy new. In lower-income countries, the second-hand clothing market is a way to aspire wearing branded clothes but at very reasonable prices. However, local, and sometimes fast fashion options are equally good. Owning a used item as ‘vintage’ has an altogether different underlying sentiment. The purchase is not for use, but of an asset, with perhaps the expectation that it will be priced even higher later on. Or perhaps to collect a rare item. In addition, the ‘vintage’ items are usually the luxury clothing pieces that were limited edition and therefore, limited in quantity. It is the fast-fashion clothing that neither sells as a rarity on the resale platforms nor is often suitable for more than one use.

The reports available on second-hand resale statistics also mention that a large proportion of customers desire fresh styles frequently, making the trend counter-productive and the exact opposite of what sustainability would conventionally mean.

But these are not even the biggest issues with this market. The very fact that search costs for used clothing will increasingly become lower and prices of used clothing have been spiked up, will not just increase demand for used clothing dramatically but lead to a very interesting outcome eventually. In her 2003 paper on the same subject, Valerie Thomas argues that the above two factors (search cost and price of used goods) lead to various relations between second-hand and new goods markets2. Declining search costs and high resale prices would eventually lead to no waste of used goods and the supply of used goods would come only from the new goods market. This is precisely what we might expect for the resale clothing market as well. The presence of online platforms has dramatically lowered the cost to look for used clothing (catering more to Gen Z) and the pricing of these products is expected to be higher than if sold conventionally.

Not all used clothes go on sale in thrift stores. A large proportion of the used clothing is exported to lower-income countries from the US and Europe. Barring this piling waste, there is also tremendous amounts of clothing that goes unsold in thrift stores and the offline resale market. Suppose some of this unsold inventory at thrift stores gets sold on online platforms. At some point in time, two things will most likely happen. The supply of trendy clothes coming from thrift stores will decline (assuming no new supply goes to thrift), and the used clothes market will then depend on the new clothes market to fuel its growth.

Very simply, the resale-at-scale model is perhaps not the best way to reduce waste in the industry. Resale is not entirely circular, but perhaps a smaller loop in a linear model. Each product has a definite life and would eventually be discarded after any number of uses. The key issue is about complementing re-using with reducing the supply of new. Unless the focus is fully on the latter, can we be sure of how sustainable the industry could become?

_Big.jpg)

Comments