Recent events—the COVID-19 crisis followed by the new post-virus industry—have forced both importers and their factory suppliers to re-examine global trade, across the board. Economists, politicians, corporations and professionals are all debating the future of globalisation.

At one extreme some believe that globalisation is at an end. Their arguments are based on the belief that globalisation has made the supply chain increasingly fragile. The want of some basic computer chips brought serious disruption to the global automobile industry. Problems with logistics increased the costs to the point when shipping a T-shirt by sea cost more than the entire FOB price.

Others believe that these are but the first examples of supply chain disruption resulting from the change to the new post-virus global economy.

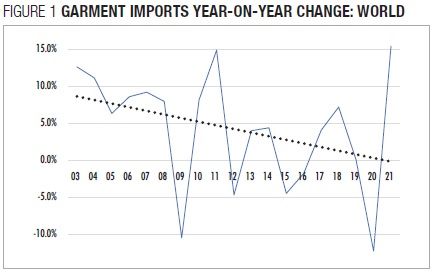

The textile/garment industry has its own perspective. Garments are the world’s most globalised industry. Nevertheless, from Figure 1, for at least the past twenty years global garment import increases have been moderating, while global GDP has been steadily increasing. The result is that over time international garment trade has become less important.

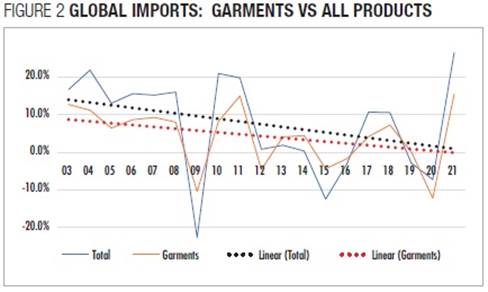

Ironically when we look at total product imports, we see an even more remarkable trend. As we can see from Figure 2 the trend in garment imports is mirrored in the trend for total product imports. In a real sense, the move away from globalisation is not a recent phenomenon, but has been a trend for over a generation.

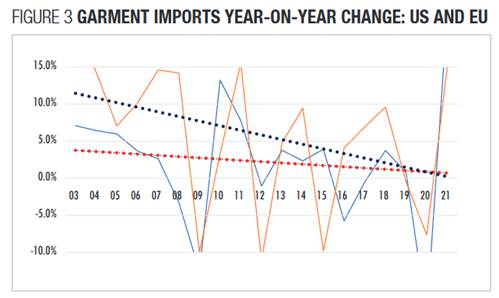

Once we recognise that what we are facing is both a global and a long-term trend, we can look further to understand just what is happening. For example, as we can see from Figure 3, the problem may be global but not necessarily universal. The EU has shown serious declines, while imports to the US have remained relatively stable.

This leads us to the second issue, the degree to which importers are moving from globalisation to reshoring and nearshoring.

The EU

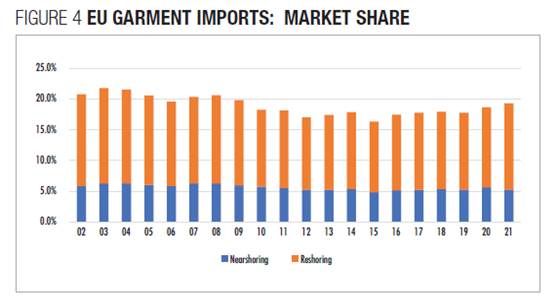

The EU has been involved in reshoring and near shoring for many years. As we can see from Figure 4, reshoring (increase in intra-EU garment imports) and nearshoring have accounted for approximately 20 per cent of EU imports at least as early as 2002.

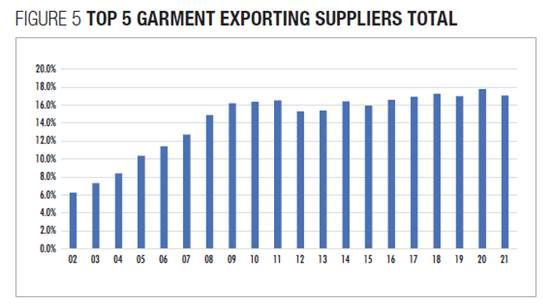

When we consider Figure 5 – garment imports from the top- 5 exporting suppliers (China, Bangladesh, Cambodia, India, Vietnam) – we can see the importance of nearshoring/reshoring compared with garment importing.

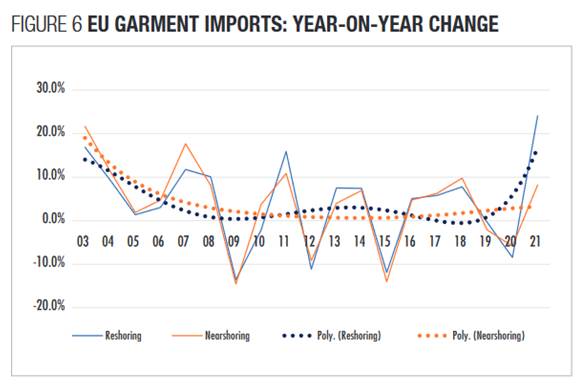

Finally, as we can see from Figure 6, recent trends indicating substantial increases in reshoring.

The US

The greatest problem facing the US is that with over 95 per cent of all garment retail sales derived directly from imports, it has virtually no domestic industry. As a result, reshoring is not an option.

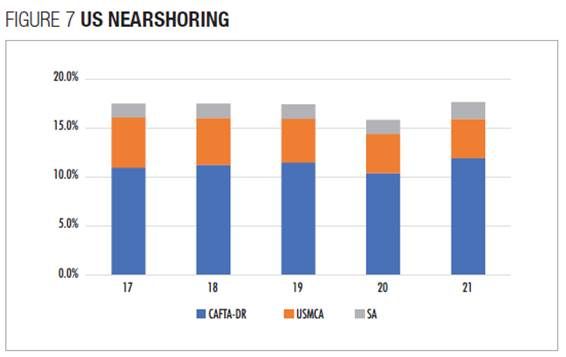

The US has but two alternatives: Nearshoring and continued importing from its existing overseas suppliers.

As we can see from Figure 7, nearshoring from all sources totals 17.6 per cent, of which 11.9 per cent is derived from CAFTA-DR, 4.0 per cent from USMCA and only 1.7 per cent from South America.

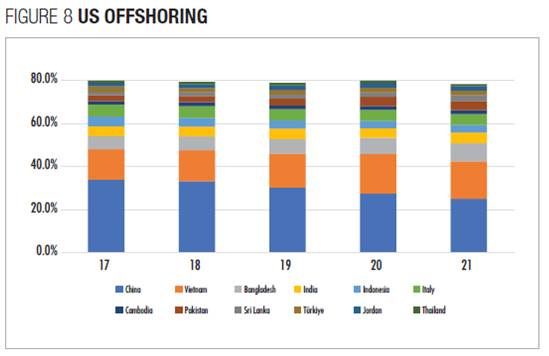

Compare this with Figure 8, which shows 78.5 per cent derived from major offshore suppliers.

This confirms the earlier Figure 3 (Garment Imports Year-on- Year Change: US and EU), US imports from offshore suppliers has changed little in the past 20 years.

Textiles

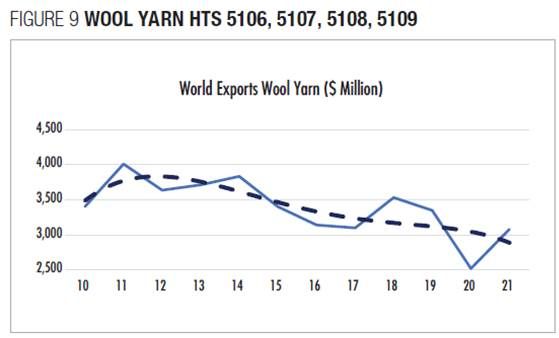

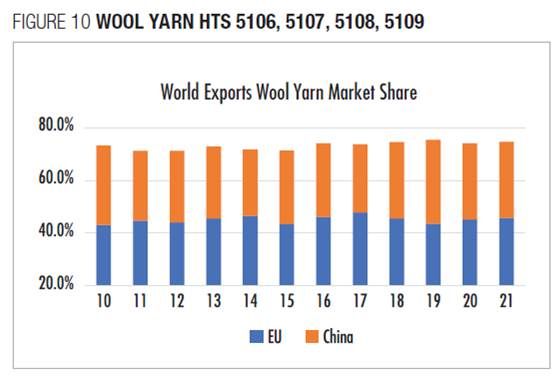

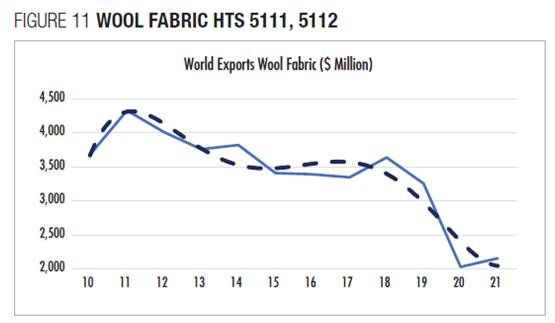

Wool HTS 51: As we can see from Figures 9 and 10, exports of wool textiles have been in a long-term decline.

As we can see from the Figure 10, exports have been dominated by the EU (45.8%) and China (28.8%)

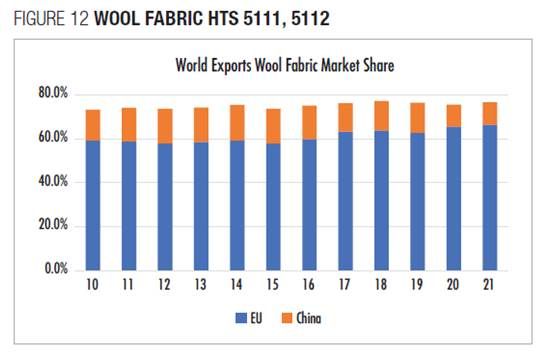

Figure 12 shows that wool fabric exports have also been dominated by the EU (66.5%) and China (10.1%).

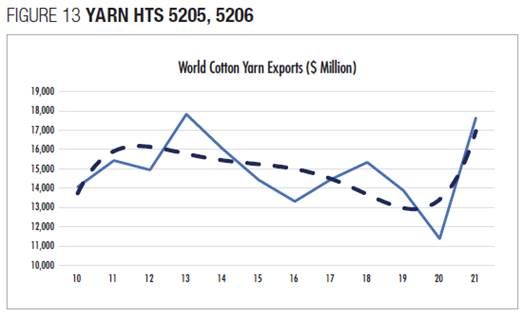

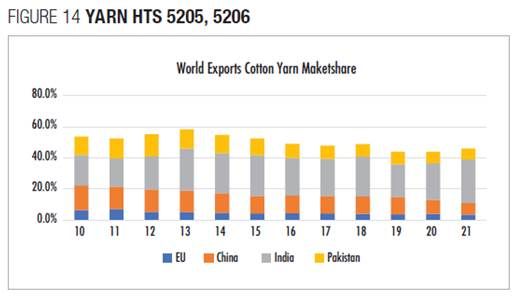

Cotton HTS 52: As we can see from Figures 13 and 14, exports of cotton textiles have been in a long-term decline despite a spike in 2001.

Yarn exporters are more diversified, but for the most part located in Asia. EU accounts for a very small portion.

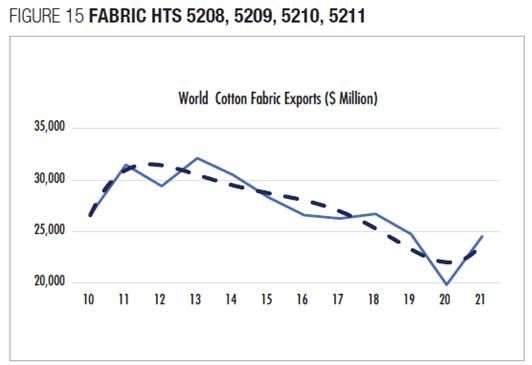

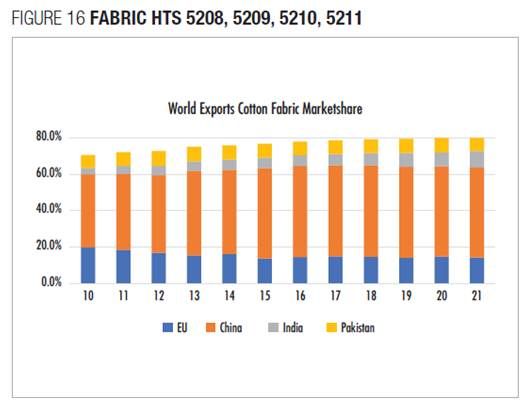

As we can see from Figures 15 and 16, exports of yarn follow a different path than exports of fabric.

Fabric exporters are more restricted with EU as a major player, second only to China, with major yarn exporters such as India and Pakistan playing only a secondary role.

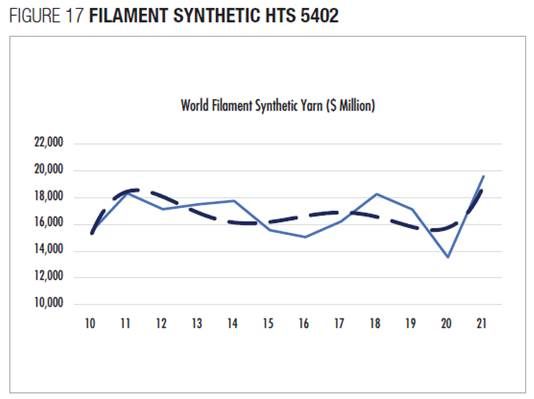

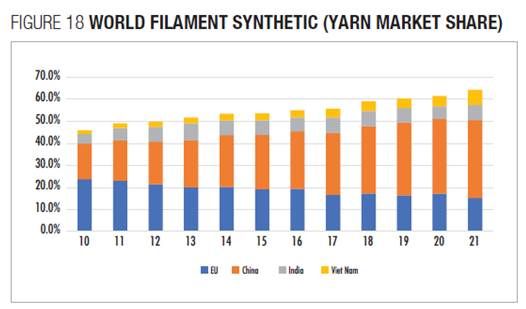

Filament Synthetic HTS 5402

Yarn: As we can see from Figure 17, exports remained relatively stable until 2016, after which exports began to increase.

As we can see from Figure 18, China has become the world’s major supplier with market share moving from 16.2 per cent in 2010 to 35.2 per cent in 2021.

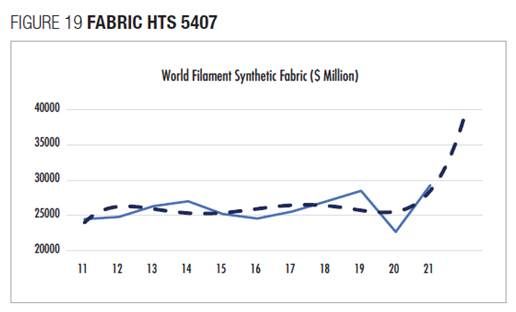

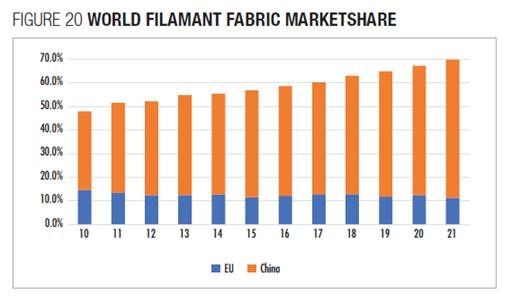

Fabric HTS 5407: As we can see from Figure 19, exports have remained stable for many years, with the exception of a spike in 2021.

As per Figure 20, China dominates export market share followed by EU. Together they account for 69.8 per cent of total exports.

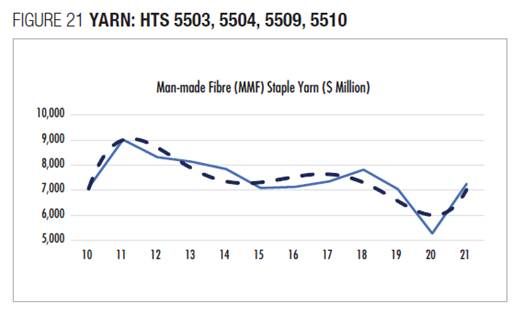

Staple Synthetic HTS 55: As we can see from Figure 21, exports peaked in 2010 and then went into a slow decline, despite the spike in 2021.

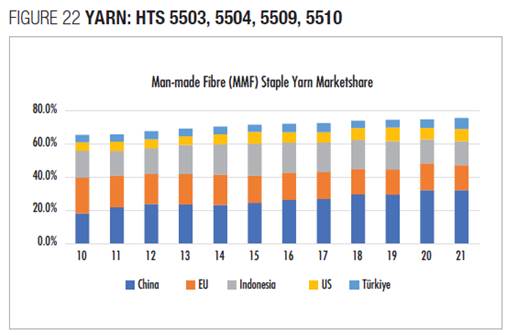

As per Figure 22, Market share has been dominated by three suppliers – China, EU, and Indonesia – which collectively account for 61.5 per cent of all exports.

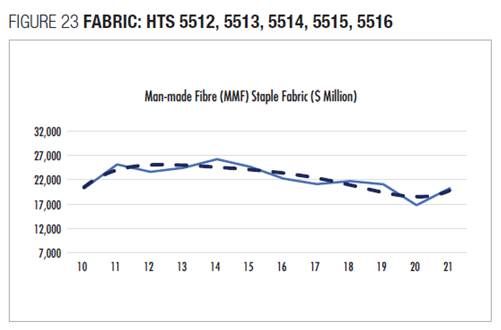

As we can see from Figure 23, exports after peaking in 2010 have gone into a state of decline.

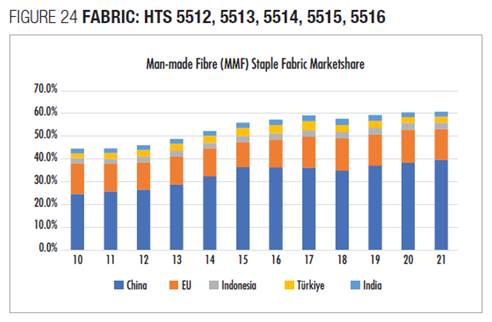

As we can see from Figure 24, China and EU dominate with a collective market share of 53.2 per cent.

From Globalisation to Regionalisation

From the data above, we can conclude that the global textile trade is dominated by two suppliers: China and the EU. Given the risks of globalisation, from the point of view of both the importer and exporter, regionalisation makes sense, i.e., putting a stop in trying to increase trade to suppliers located half-way around the world, and moving closer to home.

Going forward we can expect that garments produced in Asia – particularly in the moderate and low-price sectors – will source fabric from China, while garments produced in the West – particularly in the higher priced sectors – will source fabrics from the EU.

Once again, the US will be the exception. With virtually no domestic industry, reshoring is not an option. Indeed, since US imports from the region are limited to low price commodities, it would appear that nearshoring is at best a limited option. Under the circumstances, the US will have little options and will be stuck with the traditional global sourcing model with its inherent risks.

The EU at least to some degree enjoys an advantage. Countries such as Morocco, Tunisia and Egypt have growing garment exporting industries.

From Regionalisation to Reshoring

Those who see the end of globalisation look towards autarky. Theoretically, this is the universal panacea. STOP IMPORTING, PRODUCE EVERYTHING AT HOME.

Note: Data for all figures extracted from websites of US Government Office of Textiles and Apparel (OTEXA), International Trade Centre (ITC), Trademap.org, and HTS numbers https://hts.usitc.gov/current

Comments